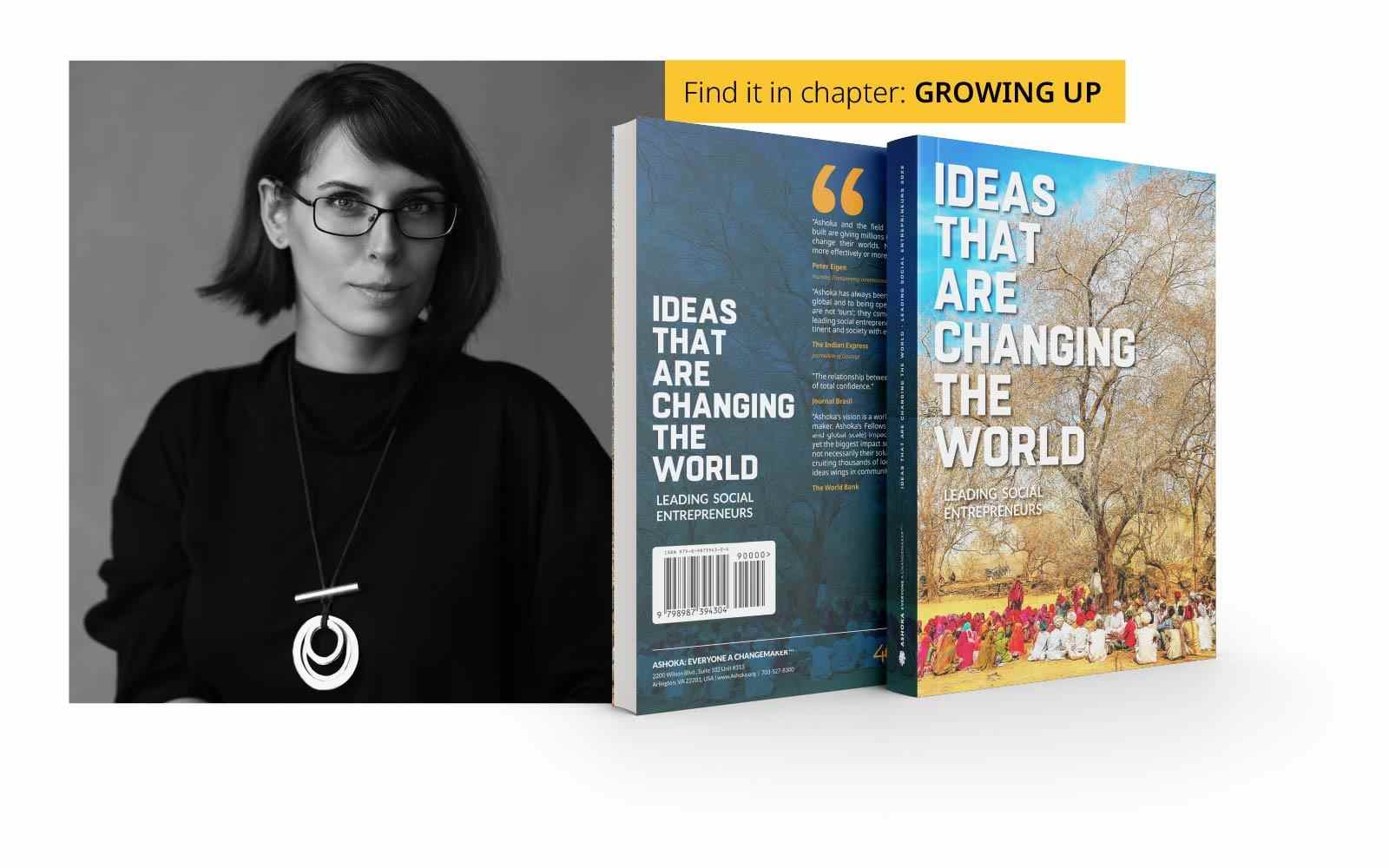

Iarina Taban

Director and Founder, Ajungem Mari

Fellow project website:www.ajungemmari.ro

When communism ended in Romania, images of neglected children found in overcrowded orphanages shocked the world. In response, Iarina founded a national network that marshalled volunteers, helping professionals, and other resources to serve the long-term educational and developmenal needs of institutionalized children and youth. Her work not only changes their lives; it changes the care system and shifts intergenerational patterns of trauma, poverty, and institutionalization.

THE NEW IDEA

Iarina Taban engages and weaves together committed volunteers, care staff, educators, specialized helping professionals, and other resources into a dynamic, creative team of teams and a community of care serving the developmental needs of institutionalized young people. Her approach empowers participants to become change-makers in the lives of Romania’s disadvantaged youth and its institutional care system. Together, they are not only transforming young people’s lives, but also mindsets, institutional cultures, and the care system itself.

A legacy of the communist era, Romania has one of the largest institutional care systems in Central and Eastern Europe. Orphanages with outdated facilities and approaches still operate there.

Youth in state care often experience trauma, have low levels of educational attainment, and lack social integration outside the institution. Iarina recognized that as they aged out and left the institution, the cycle of poverty, trauma, and institutionalization would likely continue into the next generation – especially if they had children themselves – – unless they were shown a different path.

Iarina forged one. She co-founded Ajungem Mari or Growing Great, Romania’s only national program dedicated to the broader educational and developmental needs of institutionalized and disadvantaged youth.

Existing care institutions in Romania serve young people’s immediate needs like food and shelter and provide a basic level of education. But Iarina’s work recruits and equips volunteer “life mentors” to serve their critical developmental needs, providing the key dimension miss-ing from institutional care: emotional bonding with a trusted, caring adult who can be a consistent, long-term presence and a positive role model, and provide a bridge to an independent life beyond the institution.

Mentors undergo specialized training in how to build trust and lasting relationships with young people who have been through trauma and are connected to a network of psychologists, educators, and other professionals who lend their expertise and support. Mentors have creative licenses to implement their own ideas about how to customize their activities to meet mentees’ needs, but they also have to work within the rules of state care institutions.

Volunteering is not common in Romania and where it occurs, it’s typically short-term. But Iarina has managed to attract a growing number of citizens to volunteer for long stretches of time and commit to changing the lives of institutionalized children. Mentors volunteer for a minimum of eight to 12 months – enough time to establish a consistent presence in the life of a child and to form a secure attachment to a significant adult. But the bond typically lasts for years, until after they leave state care. This is transformative for young people, and for mentors as well.

Growing Great has engaged 8500 volunteers so far, with than half of life mentors still engaged with their mentees years later. Exposure to the close relationship between mentors and children also influences state care workers, sparking their interest in adopting a similar approach.

Iarina works to foster that, offering state care workers training and support resources. She encourages them to reframe how they see their role, not as “prison guards” or low-level vocational trainers, but as as caring, mis-sion-driven professionals providing emotional support for institutionalized youth.

THE PROBLEM

Over six million children live in institutions worldwide – the majority of them in low – and middle-income countries. Institutionalization profoundly affects children’s physical and psychological development and is associated with long-term mental health problems. Care institution staff typically have little training, low pay, and high turnover. This hinders effective relationship building and is often insufficient to provide a basic standard of care.

In Romania, the problem is especially pronounced. In the communist era, poor families were encouraged to leave their children in state care, especially children with disabilities. When the communist regime ended in 1989, over 100,000 children were in living in state institutions. More than 16,000 children in state care were dying each year from treatable diseases and other causes.

Since then, care facilities and conditions in Romania improved, and the number of children in state care has fallen. But institutionalization remains widespread and still negatively impacts young people’s health and development.

Five thousand children and young people enter Roma-nia’s childcare system each year. In 2018, there were about 60,000 children in the state foster care system, of whom 18,500 were in state-run institutions, many of them ending up there because of family poverty, abuse, or neglect. Inside the system, many suffer from abandonment trauma, experience new or restimulated trauma, and act it out, engaging in negative, risky behaviors and sometimes becoming abusive or violent themselves.

Understanding and effectively working with their needs require specialized training that staff and educators at state care institutions rarely have. They are often stretched impossibly thin, with 30 or 40 children per orphanage, and 60-70 children per case manager. Institutional culture is not geared toward developmental needs, fostering meaningful emotional bonds, or delivering personalized care. In fact, working in these challenging environments and constantly being exposed to children’s trauma, care staff are at risk for experiencing trauma themselves.

Though much reduced since the fall of communism, corruption’s lingering influence tends to make state care institutions untransparent and highly political. It’s common practice for employees to write detailed reports that don’t acknowledge problems, tell officials what they want to hear, and give the impression of perfect conditions in order to maintain the status quo and protect their funding. Consequently, institutionalized young people don’t get the support they need to build life skills, pursue their education, make good decisions, and become functional, independent citizens. Two-thirds of those who age out and leave state care lack any occupation, and only 15% continue their education in any form.

This leaves them disconnected from society and puts them at high risk for poverty, homelessness, and human trafficking. Girls in Romanian state care institutions are particularly targeted by sex traffickers. Trafficking is by nature global and reliable data is scarce, but Romania ranks among the top five EU countries for the number of registered trafficking victims and ranks first for the number of reported persons arrested, cautioned, or suspected of trafficking.

Ajungem MARI, the only national program that supports the long-term education of institutionalized children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, has started a new volunteer recruitment campaign. Children and young people in the protection system in Romania need people to support them, understand them, and give them confidence. - rfi ROMANIA

When formerly institutionalized children in Romania have children of their own, they often abandon them, re-capitulating a cycle that leads to institutionalization and subsequent negative outcomes.

Such problems aren’t unique to Romania; they’re global. According to UNICEF, lack of individualized care and the lack of a healthy bond with an adult figure are key factors inhibiting essential psychosocial development of children in institutions worldwide, which in turn leads to negative outcomes in adult life.

Since they aren’t getting what they need inside care institutions, it stands to reason community members outside these institutions could be a resource to help young people integrate into society successfully. But lingering influences of communism have also made this culturally difficult in Romania.

Communist officials required Romanians to “volunteer” for national celebrations and other activities mandated by the government. This fostered resentment rather than feelings of personal responsibility or desire to serve the community. As a result, volunteerism was widely considered a waste of time, and socially engaged individuals were dismissed as “village fools.” This attitude persists today, especially among the generation that remembers life under the communist regime.

THE STRATEGY

Iarina built a diverse team of teams for the welfare of institutionalized children that brings together volunteer mentors, care staff, educators, and helping professionals.

She co-founded Growing Great in 2014 and started recruiting volunteers in the Bucharest area as “life mentors” for young people in the state childcare system. Today, 3000 prospective volunteers across Romania, ages 16 to 65, apply to be life mentors each year.

Connecting community members to institutionalized young people is shifting norms and nurturing a growing desire for community service and volunteerism. At the same time, connecting care staff and educators to the network of volunteers and expert resources is shifting the care system toward meeting children’s developmental needs.

Educators and care staff are connected to volunteer mentors in their area, invited to online support groups, given access to psychologists to advise them as needed, and offered certificates for completing training in subjects institutionalized youth need to learn about, such as online safety, civic education, financial literacy, sexual education, and more.

County-level mentoring communities self-organize into peer-to-peer learning networks with their own coordinators, debriefing and supporting each other on their work with children.

Life mentors commit to spending at least two hours a week with the children for a minimum of eight to 12 months. That may not seem like a long time, but given the relative lack of volunteerism in Romanian society, it’s actually an ambitious place to start. And for most, it’s just the beginning. The majority of Growing Great life mentors stay engaged with their mentees for three to five years, motivated by a genuine mutual bond, rather than the initial volunteer commitment.

Iarina Taban is the founder of the Ajungem MARI Educational Program for children from foster care centers and disadvantaged environments. Since 2014, her team has attracted thousands of volunteers to be with institutionalized children for the long term. - REPUBLICA

“Children in foster care need relationships with people who understand, listen and accept them as they are, people they can trust, says Iarina. “And trust can only be built over time, by keeping promises.”

Life mentor applicants undergo a rigorous psychological clearance and orientation process, then an eight-hour training program on safe and effective ways of communicating with the children, handling tense situations such as fights, and developing educational activities. They are then tested to determine how they would react to various situations – i.e. encouragingly or judgmentally. Those who make it through the vetting process sign contracts, are partnered with another mentor, and they are assigned to children in the state care system.

Mentors work in pairs, supporting and keeping each other accountable. Starting by helping children with their homework, they build trust and learn more about their mentees’ needs and desires, then create a personalized program around them. Helping professionals in Grow-ing GREAT’s network – educators, vocational trainers, psychologists, speech therapists, etc. – – are available for individual courses, one-on-one tutoring, and therapy sessions. Mentees are also offered internships and local extracurricular activities that help them explore a wide range of interests (circus school is one example) as well as trips, summer camps, and social activities that connect them to and prepare them for life outside the institution. During the pandemic, Growing GREAT tapped its networks to offer children a rich array of online courses in dance, theater, singing, and robotics, among other subjects.

Life mentors are free to innovate and create their own individualized programs for mentees, but they also must understand and operate within the rules and protocols governing state care institutions. Mentors file paperwork on their interactions with children, which is compiled and tracked by Growing GREAT, helping build trust with care institutions. Proposed activities need sign-off from the institution’s director or from county officials, and life mentors are encouraged to work closely with them, exchange ideas, and cultivate collegial, two-way relationships.

The experience of mentoring and the bonds life mentors form with mentees can be just as transformative for them as for the young people they serve. In fact, some mentors have adopted their mentees. Others changed their careers to become teachers, psychologists, and therapists for disadvantaged children.

“For three years, on Mondays at 4 pm, I would arrive at the care home, and they would be at the window, waiting for me,” said one life mentor. “The children have grown up, but I feel that I have also grown up. I learned new things with them, I attended classes to keep up with them, and I had to read more myself so I could answer their questions. I met open-minded, young people who gave me confidence in myself. I saw that there is room for everyone, any helping hand is welcome, and any skill can find its usefulness.”

The end of the mentor-mentee relationship is handled with care. Since life mentors work in pairs, if one of them must stop volunteering, the other can maintain their bond with the child. And whenever a mentoring relationship ends, the Growing GREAT community facilitates a comprehensive closure process where mentors let the child know what they love and appreciate about them. The process allows for healthy separation and prevents further trauma for the child.

Partnering with other civil society and public sector organizations, Iarina recently launched an independent living guide for young people, mentors, and teachers. It has practical information explaining young people’s options and legal aspects as they age out of the care system, which they otherwise wouldn’t know. For example, the guide points out they can stay in care centers until age 26 if they are studying or have a job.

But even as they prepare to leave the system, many have trouble making decisions and directing their lives. Iarina puts particular emphasis on providing resources to help them transition out of state care and establish themselves in the world, such as vocational counseling, professional training courses, site visits to explore different jobs and help with getting driver’s licenses. One measure of her success is that children who went through the Growing GREAT program have even gone on to become life mentors themselves.

Launched in Bucharest eight years ago, Iarina’s model was designed for rapid uptake. In 2016, Romania’s Ministry of Labor recommended the Growing GREAT be extended to as many vulnerable children as possible. Today, it has expanded throughout the country. Organizations in the Republic of Moldavia are also working to spread Iarina’s approach. So far she has engaged over 8,500 volunteers contributing over 500,000 hours helping children in over 220 state care facilities.

With mentoring communities widely established, Iarina is focusing on her role as a field builder, including by deepening her relationships with and support for workers and educators in state care facilities. Their own trauma from working in these settings needs empathy and redress in its own right, so that they can be more fully present to children and become changemakers within the care system. Iarina uses online learning tools to engage state care employees, foster a closer relationship between them and life mentors, and create a better environment for institutionalized children.

THE PERSON

As the only child of well-educated parents, Iarina was instilled with a sense of the importance of education and won national prizes for creative writing.

She started volunteering in high school and in her first year of university joined the Volunteer Brigade, where she coordinated volunteers at concerts and festivals. In a culture where volunteering had not been valued historically, the experience convinced her that a critical mass of volunteers could achieve meaningful change.

In her early 20s, Iarina worked as a communications staffer for an English language education company. She was given the opportunity to oversee a pilot project for which she recruited, trained, and coordinated 27 volunteers to teach English using non-formal methods for disadvantaged children in Bucharest daycare centers. The volunteers were high school students. Working two hours a week with the same group of children, she came to realize that the relationships they formed with the children had other benefits besides improving their English. The children demonstrated higher self-esteem, more motivation to learn, and better-developed social skills.

The next year many more volunteers signed up and the project was set to expand to three more counties. But the company didn’t support the effort properly, so Iarina quit her job to start her own volunteer education project for disadvantaged children. She left with 150 euros in her bank account, a small group of close friends who offered to help, and zero restrictions on her creativity.

At age 25, she made her first visit to a state care institution. She was shocked by the continuous screaming of a three-year-old boy who was abandoned at birth and then abandoned again by a foster parent. The suffering and loneliness of the children she encountered there, most of whom couldn’t even express their feelings, was over-whelming. The experience crystalized Iarina’s mission to revolutionize and humanize care for disadvantaged, traumatized children.