Introduction

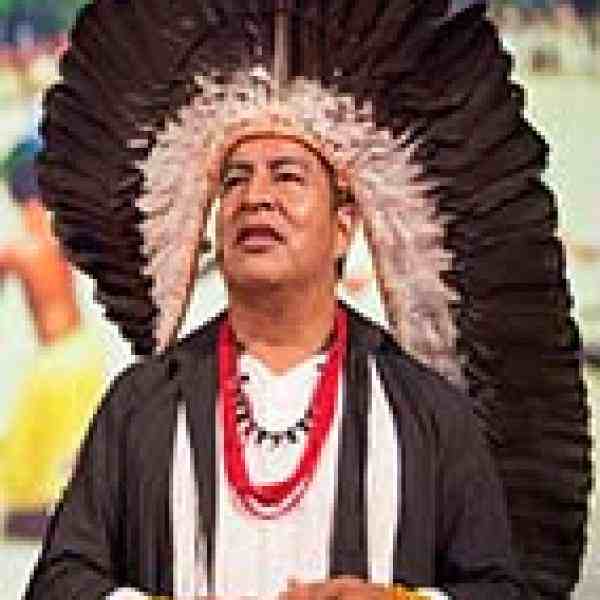

Tashka Yawanawá works to restore the dignity and sense of identity of indigenous communities in Brazil through a series of cultural revitalization efforts and innovative business partnerships—proving that maintaining cultural integrity need not conflict with achieving economic prosperity.

The New Idea

Tashka has developed a unique two-step methodology to facilitate both the economic and cultural revitalization of today’s indigenous communities. He begins with a host of activities and interventions designed to celebrate the traditions and values of the community. The goal of these efforts—including a week-long festival that features the artistry, traditions, and history of his people—is to alter the community’s own definition of wealth, and to counter the notion that they are mired in misery and poverty. Equipped with a renewed sense of self-worth and a clear understanding of their assets, the community members then identify ways in which they can use their cultural resources to fuel business deals on their own terms.

Rather than accept their role as the mere suppliers of raw materials, Tashka forms business partnerships with outside commercial enterprises with an explicit mutual benefit. Emphasizing the spiritual and cultural values of his people, he aims to influence the decisions and strategies adopted by his business partners, and to fuel strengthened consumer consciousness. Each of these pieces feeds into Tashka’s larger goal: To break the decades-long history of reliance on outside organizations and institutions, and in so doing, to empower indigenous communities through enhanced information access. To this end, he has developed a series of partnerships to facilitate information exchange between members of his community and various corporate, government, and social sector partners, so that future generations will possess both deep cultural knowledge and a modern education.

Having spent several years in the United States, Tashka inherently understands the forces at work in both his and the Western worlds. As a result, he serves as an unusually effective bridge between indigenous groups and the outside. Thanks to his efforts, the Yawanawá today maintain a balance between the modern and traditional: Enjoying a combination of strengthened spiritual and cultural identity, secured land-rights, and improved income generation, thanks to more effective, community-driven use of natural resources. Recognizing that most indigenous groups face many of the same challenges, Tashka is furthermore sharing his tribe’s experiences with other communities. Already, several other indigenous groups have replicated the festival in their own communities. Through partnerships with a variety of national and international institutions, Tashka aims to strengthen the ties between currently disjointed indigenous tribes, and to demonstrate to all in the outside world that it is possible to both maintain one’s indigenous heritage and to do business within today’s globalized world.

The Problem

For most indigenous communities exposed early on to European settlers, initial contact with outside civilization was characterized by widespread disease and conflict, decimating their population even as they struggled to maintain their power and autonomy. This period was typically followed by massive resource exploitation and widespread subjugation, as the rubber trade and other extractive industries took off. As a result of such foreign conquests, indigenous peoples became increasingly mired in dependency: A situation made all the worse by the arrival of Christian missionaries, who denied them the right to speak their native languages and to exercise their spiritual beliefs and cultural rituals. According to estimates by the National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI), of the 1,000 indigenous languages that existed prior to contact, only 160 are still spoken today. Indeed, there were an estimated 40 million people living in Brazil when Europeans first arrived; today, the indigenous population stands at between 700,000 and one million.Beginning in the 1980s, the indigenous movement emerged in an effort to counter this system of oppression. Focused primarily on securing land rights, however, the movement has been limited in scope, and as a result, has failed to fully address the dependency generated earlier. Indigenous tribes continue to rely on their state governments for health and education services and all processed goods, and have yet to find a model of development that secures both their economic well-being and their centuries-old values and way of life.

Having first come into contact with European rubber barons in the nineteenth century, the Yawanawá have experienced many of these struggles throughout their own historical evolution. Like so many others, the tribe came to depend on rubber extraction as its sole source of income, and thus experienced considerable economic hardship once demand for Brazilian rubber subsided. As a result, they have little access to effective education and health services, which only works to fuel the cycle of dependency. The effects of the rubber boom thus continue to play a profound role in economic development efforts today, as the labor and economic systems of the Yawanawá have proven fundamentally incompatible with those that have been imposed upon them. Indigenous communities, meanwhile, lack access to the necessary knowledge and information to bargain effectively with outsiders, and as a result, most business partnerships formed between indigenous communities and corporate entities are inherently skewed in the favor of the outside party.

However, it is the psychological impact of this dependency and the loss of identity that it entails that has proven the most costly. Today’s indigenous people, especially the young, find themselves displaced between two worlds, severed from their cultural roots. Taught to believe that their own cultures are “backwards” or out-dated, many young people leave the community only to find themselves at odds with the modern urban landscape. Stigmatized by their non-indigenous counterparts, today’s young indigenous people lack the same appreciation for the history and significance behind their long-practiced rituals enjoyed by their elders. As a result, the very existence of the Yawanawá—and other indigenous groups elsewhere in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador—has come increasingly under threat.

The Strategy

After four years spent studying in the U.S. and visiting other indigenous communities throughout the Americas, Tashka returned home to the Yawanawá with plans to focus immediately on economic improvement. He soon realized, however, that in order to secure his community’s economic independence, he would first need to restore their fundamental sense of self-worth. In an effort to counter the widespread disrespect shown toward the aged in the community, Tashka asked the elders to recall what life was like before contact, reminding them of their lost cultural vitality and strengths. He then urged the community to consider where they wanted to be in 100 years, and helped them to draw a path to achieving it. This planning period culminated in 1995 in the first Yawanawá Festival: A weeklong celebration showcasing the community’s long-forgotten ceremonies, rituals, artistry, and rich cultural inheritance. By sparking a cultural renaissance, the Festival served to restore the community members’ pride in themselves and their culture. Currently in its seventh year, the Festival continues to be held purely for the tribe’s benefit; though it attracts widespread media coverage and government attention, this, too, serves primarily to fuel the sense of pride felt by community members of every age.

Tashka then turns his focus to building business partnerships that better use the community’s natural assets, and that can thus be negotiated on the Yawanawá’s own terms. His first major project entailed changing a decade-long relationship between his tribe and the cosmetics company Aveda, to supply urucum—a local fruit used as a lipstick color. Handled through an intermediary, the relationship had long been exploitive and riddled with corruption. Tashka met with the President of Aveda, explaining the need for a direct relationship with the company and a contract to protect and promote the tribe’s image. Moreover, recognizing that the profit-driven demands for ever greater production were wholly out of line with the values and lifestyle of his people, Tashka demanded that the partnership proceed on the community’s terms, and that they limit the amount of urucum produced. This marked what was perhaps the first assertion of the right of an indigenous group in Brazil to partake in the same rules of business as their non-indigenous counterparts. It has had a direct influence on Aveda’s approach with its other indigenous business partners.

It was during the first Yawanawá Festival that Tashka began to explore further opportunities that would combine his tribe’s social values with its economic interests. Recognizing the untapped economic potential in the unique artistry of his tribe’s traditional body painting—a practice that was already beginning to disappear at the time—Tashka chose to partner with a Brazilian designer, the government of Acre, and Rainforest Concern, a CO based in the United Kingdom, to create the Yawanawá brand. Now featured in its fourth collection, the Yawanawá brand captures the tribe’s designs in t-shirts, skirts, and other apparel. By helping consumers realize that there are people behind the products they freely use, Tashka also enhances consumer consciousness and fuels demand for products with a built-in social component. He has even formed a partnership with Wal-Mart to sell the clothing line in its stores, bringing both increased resources and enhanced visibility to his community, while helping Wal-Mart to improve both its image and legacy.

His work to capture the community’s natural assets does not end here. Recognizing the immense wealth of medicinal knowledge enjoyed by his people for centuries, he is helping to catalogue more than 5,000 traditional herbs, including the formal names and uses of each, along with how his people came to know them and an explanation of the Yawanawá’s relationship to nature and spirituality. In line with his aims to increase respect toward women, children, and the aged, the two women who originally worked as his assistants on the project have since gone on to become shamans—the first women in the tribe’s history to do so.

In an effort to enable the community to collectively manage the profits earned through its various commercial partnerships, Tashka launched COOPERYAWA, a legally registered cooperative. The profits fund a range of capacity-building programs chosen by the tribe. Thus far, they have elected to build a health clinic and a school, and to purchase solar panels and a radiophone. Together with the rest of the community, Tashka has completed the basic infrastructure for a biodiesel plant that will use the oil of the andiroba tree. Breaking with tradition, he has secured women and young people a voice on the cooperative’s governing board, ensuring that its representation reflects the make-up of the six villages.

By improving the quality of life in the community, Tashka aims to break the one-way population migration to Brazil’s more urban areas and to ensure that even those who study outside the community will ultimately choose to return. To this end, he has created a series of partnerships designed to facilitate better information exchange. Using an existing relationship between the government of Acre and that of Cuba, he helped to secure four stipends for members of his community to study medicine in Cuba, where there exists a well-developed program to bring healthcare to the grassroots level. Through these exchanges and improved educational resources, he hopes that the next generation of the Yawanawá will possess both cultural knowledge and a modern education so that they can operate effectively in today’s economic system.

In an effort to garner further support for the cause of the Yawanawá, Tashka launched “YAWA—The Story of the Yawanawá,” a documentary made during the 2004 Festival. The film has been distributed throughout Brazil and overseas and attracted widespread public support. Tashka sought to capitalize on the international support that followed the DVD’s release to address the issue of land rights, having led a five-year campaign to incorporate the Yawanawá’s ancestral lands into its existing land demarcation. He turned his attention the Governor of Acre, leading a letter-writing campaign and public advocacy effort that left the Governor’s office paralyzed by calls, letters, and emails from supporters. The Governor agreed to a meeting, and Tashka explained that his community’s demands were non-negotiable. He did, however, agree to help improve the Governor’s image if he agreed to the changes; they took a public picture together, and the Governor has remained supportive ever since. The Yawanawá thus secured rights to a further 93,000 hectares of land: As the first such land to reallocation in Brazil, the decision has paved the way for other indigenous groups to follow suit. He is furthermore using the media as the basis for his spread strategy, through projects like a 2005 MTV video featuring the tribe and hosted by Joaquin Phoenix, which he and a friend from the U.S. produced together and has been translated in nine languages.

Once on the brink of extinction, Tashka’s tribe, the Yawanawá, scattered in six villages near the border with Peru and Bolivia, has grown by more than 300 percent in the last ten years. Tashka is now working to build ties with the other local and regional tribes living along the border of Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, and indeed, with those scattered throughout the Americas. Five other tribes have organized their own festivals and formed their own business deals, and many more are looking to the Yawanawá as a model for how to restore indigenous pride and stimulate economic growth at the same time. He has partnered with Brazil’s Pro-Indian Commission, which is helping him to publish materials in his tribe’s local language, and the Indigenous Peoples Movement, and helped to start the Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Youth Alliance, through which he shares the experience and knowledge of the Yawanawá with youth around the world. He is an active participant within the international network of indigenous movements, and regularly speaks at conferences throughout the Americas, Europe, and the UN, showcasing the experiences of the Yawanawá.

The Person

The son of the former leader of the Yawanawá, Tashka grew up well-aware of the issues of identity and disempowerment confronting today’s indigenous peoples. As a young boy, he witnessed the virtual enslavement of his people under the rubber barons and experienced the near annihilation of his culture by the New Tribes Mission, set on destroying all vestiges of the tribe’s traditional way of life.

At the age of ten, Tashka contracted tuberculosis, malaria, and hepatitis, and was so debilitated that the tribe’s shaman was unable to cure him. Dependent on the missionaries, Tashka’s father had no choice but to allow them to take him to Rio Branco for treatment—promising that, when recovered, Tashka would study in the Mission school and become a priest. Tashka went on to break ties with the missionaries and was prevented for a time from returning to his village. He then became involved with the newly born local indigenous movement in the 1980s. He discovered the existence of laws guaranteeing rights for indigenous peoples, and actively participated in the campaign for the demarcation of indigenous territories.

In 1990, with the help of the Pro Indian Commission, Tashka won a scholarship to study computer science at the Federal Fluminense University in Rio de Janeiro. Before completing this course, however, he returned to his tribe after an absence of eight years. He was shocked to find that despite their new landholdings, his people continued to live in absolute misery. While he at first wanted to stay, he was strongly advised by his father—who was himself illiterate—to continue his studies in the U.S. and abroad, so that he would be better equipped to help his people in the future.

With a scholarship from Aveda, he was able to study English in the U.S. for six months and then went on to study in San Francisco, where he became involved with the North American indigenous movement. Recognizing the commonalities in their interests, he began to develop various projects with COs in the U.S. He was directly involved in the creation of the Indigenous Lawyers Association and co-founded the Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Youth Alliance, through which he shares the experiences and knowledge of the Yawanawá with youth around the world, and works with projects that guarantee the preservation of different indigenous cultures. From the U.S., Tashka took the opportunity to visit other indigenous peoples in Mexico and Central and South America, with his wife, an indigenous Mexican.

In 2001, Tashka returned to Brazil, and chose to use the knowledge gained from his experiences abroad to help his people transform their future. At just twenty-five, he became the youngest Chief in the history of the Yawanawá.