Introduction

Inspired by the global distribution and reach of Coca-Cola products, Simon Berry has built a successful new model to bring lifesaving, over-the-counter medicines to low-income communities where they are currently unavailable. Simon believes that if suppliers create products that truly suit the needs and constraints of the people at the bottom of the pyramid, the private market can play a key role in healthcare distribution in rural or under-resourced settings. His mission is, therefore, to ensure that the correct products and sustainable supply chains are in place to enable shopkeepers and the existing health system to reliably stock affordable treatments.

The New Idea

Simon is redesigning both supply-side and demand-side factors in order to demonstrate once and for all how easy it is to treat an illness like diarrhea, which is currently the second biggest killer of children under five years of age. Across the developing world, the current top-down system of distribution through health clinics is failing to get the lifesaving treatment of ORSZ (Oral Rehydration Salts and Zinc) into the hands of mothers when their children need it. Therefore, Simon’s approach starts at the ground level, working to understand the needs of end users and together designing a new and affordable treatment for childhood diarrhea best suited for ‘at home’ use. Simon then connects this grassroots learning back to the ministry of health, development agencies, and manufacturers so they can work collaboratively to respond effectively to this demand. By catalyzing a public-private partnership, together they create a new market and sustainable distribution system for the medicine. While many supply-chain solutions involve creating a completely new entity within the chain itself, Simon, through ColaLife, is able to bring together, influence, and coordinate existing players and resources. On the supply side, his model works through the private-sector distribution networks of fast-moving consumer goods—bringing manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, and small village shop keepers together into a sustainable value chain for the health product. His non-profit also serves as a trusted bridge to the public sector; so, they work in parallel with retailers to reach mothers and change behavior in the long-term. Ultimately, Simon is decreasing reliance on public provision alone, and putting health care into the hands of more-informed citizens. Having established the economic feasibility and medical efficacy of his model in Zambia, focused specifically on childhood diarrhea, Simon’s mission now is to incorporate this bottom-up approach into other sectors of public health, and influencing public health systems, development agencies, supply chains, and pharmaceutical producers around the world.

The Problem

Diarrhea remains the second leading cause of death in children under five worldwide, killing 600,000 children each year according to conservative estimations. It is also a leading cause of malnutrition in children. Diarrhea is both preventable and easily treatable. From 2000 to 2013, the total annual number of under-five diarrhea-related deaths decreased by more than 50% (from over 1.2 million to fewer than 0.6 million). However, in remote areas of developing countries child mortality figures have not significantly changed for at least three decades, indicating that current initiatives are failing to reach the poorest and hardest-to-reach children—50% of all diarrhea related deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. Those deaths are avoidable. In fact, experts say that with adequate treatment coverage, 75% of diarrhea-related deaths could be avoided. Tackling diarrhea does not require major scientific innovation - prevention measures, and effective treatments have long been identified. Rather, the remaining challenge is how to get the solutions to those that actually need it most. Since 2004, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) have recommended the use of Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) combined with Zinc, (also referred to as ORSZ), as a simple and cost-effective treatment. While ORS rehydrates children, Zinc is effective in preventing diarrhea, and is more effective than ORS alone in limiting the duration and severity of the disease. Yet, less than 1% of children under the age of five receive the recommended treatment. In rural areas of sub-Saharan countries, only 30% of all affected children have access to ORS while Zinc remains largely unavailable to the poorest children, despite medical proof showing that the right amount and intake of ORSZ can reduce death rates by 93%. Simple measures can prevent diarrhea-related deaths. Longer breastfeeding and good hygiene and sanitation are among those practices that significantly reduce diarrhea prevalence. However, emergency treatment will always be needed. Once diarrhea strikes, rapid access to treatment can be a matter of life or death. Although the effectiveness of ORSZ as a treatment is acknowledged, there are also common bottlenecks such as awareness, availability, access, and correct use. In Sub-Saharan Africa in particular, public sector supply is erratic. Long distances and low supply have discouraged mothers from administering the routine treatment, resulting in less than 1% currently receiving ORS and Zinc when needed in rural Zambia. Furthermore, the packaging is not fit for the purpose, and leads to misuse and waste of resources. Common one-liter ORS packets, originally designed for use in hospitals, are not appropriate for home use. While any unused solution should be thrown away after a day, quantities are too large and solution is stored for longer. Moreover, a liter is poorly understood, and measuring utensils are rarely found in rural African homes. On the other hand, there is a problem around overmedicating diarrhea, leaving people under the impression that they have to go to hospital, even though treatment can be non-medical. To date, both the public and the private sector are failing to successfully supply a user-friendly treatment, leaving populations confused and millions of children dead from a treatable disease.

The Strategy

Simon’s life mission is to catalyze sustainable, appropriate supply chains for health products to reach wherever they are needed. To do this, he has focused on tackling the entrenched problem of childhood diarrhea in Sub-Saharan Africa using a three-part strategy: First, establishing a new supply chain in the private sector and kick-starting demand; Second, stepping back so that the demand is met by existing players who supply the health product reliably on the ground; And finally, working to spread the model’s key learnings into new geographies and new public health fields. The first stage in Simon’s strategy is to put in place a new private sector supply chain, and demonstrate that it can lead to change in behavior for the end user. This stage includes designing new, appropriate products where they are lacking. By working with mothers on the ground in Zambia, Simon developed a user-led design process to create a new at-home treatment kit. This is a radically new design compared to available products. It includes: co-packaging ORSZ for the first time in the region; manufacturing single-use packets, rather than the large packets available for use within health clinics; defining an affordable price; as well as including clear user instructions, aspirational branding, and functioning as a measure for water. To keep costs low and bring in the best design possible, Simon also uses an open innovation approach, publishing his briefs online and receiving feedback on design. ColaLife’s role in re-thinking design and supply chains is crucial for setting up a new market—as on-the-ground perspectives are currently failing to reach large pharmaceutical companies or even health professionals due to how they choose to allocate limited R&D resources – a trend Simon hopes to reverse by proving the efficacy of his user-led approach in catalyzing health markets at the bottom of the pyramid. Simon’s strategy, then, works through private-public partnerships to kick-start consumer demand during the launch phase of the new product. ColaLife partners with a credible local NGO that has strong existing relationships to local people, in order to oversee the initial pilot on the ground, help measure effectiveness, and educate both consumers and retailers. Simon also knew from day one that he must carefully broker the support of the Ministry of Health and local health centres for his initiative, because they too dedicate health workers’ time to getting the message out about the anti-diarrhea treatment and why it is important for child health. ColaLife’s model, then, educates rural shopkeepers to promote their product, para-skilling them in why, when, and how mothers and carers should use the anti-diarrhea kit so they become a key player in consumer education and the health system. In the launch phase, awareness is also catalyzed by distributing redeemable vouchers to mothers, and these initial activities are subsidized by partnerships and donations to ColaLife. To demonstrate the efficacy of his approach, Simon launched the health kit in two districts in Zambia, with a trial ending in September 2013. This pilot was carefully evaluated, defining pre- and post-trial benchmarks and using a control district to compare the health results. Treatment rates for children went up from under 1% receiving ORSZ when needed to 45%, with the sale of 26,000 kits to rural families. The average distance to reach treatments decreased from 7.3 km to 2.4 km, getting significantly closer to Simon’s vision of providing affordable, doorstep health products in rural areas. The correct mixing of the medicine went up from 60% to 93%. Most significantly, the perception of ORSZ as an effective treatment for diarrhea went up by 14 percentage points. Therefore, Simon’s model is crucially shifting both behavior and beliefs on the ground, where previous education initiatives have struggled. ColaLife’s research suggests the Zambian market for ORSZ would be 7 million kits per year; Ultimately, Simon’s aim is to achieve 40% treatment rates across the entire country. After catalyzing a new market, the second stage of Simon’s strategy is to encourage local actors to supply the product sustainably. ColaLife has helped to set up a truly sustainable local supply chain, where producers, distributors, and retailers each receive a small margin of profit. He has opened up the design of the treatment kit to his Zambian pharmaceutical company partner free of charge, which has now produced over 75,000 kits independently. Simon has also lobbied them to manufacture Zinc in Zambia, as this previously needed to be imported. Now, the treatment kit is locally-sourced as much as possible, leading to job creation and lower costs. Demand has stayed high from consumers, pulling more orders into the system. Recently, a major regional supermarket chain has agreed to stock it. Having witnessed the efficacy of the kit, the Zambian Ministry of Health is currently in the process of adding ORSZ to its essential medicines list, and has ordered 452,000 non-branded versions of the kit to distribute free of charge to mothers from health centres, thereby guaranteeing the availability of ORS and zinc together to decrease current public sector shortages. External evaluators have estimated that 3 lives are saved per 1000 kits sold; therefore, this order alone would save more than 1300 lives, and significantly impact malnutrition rates for children. ColaLife has also used crowdsourcing to raise the money necessary to provide discount vouchers to poor mothers who feel they cannot afford the treatment during the product launch phase. Ultimately, Simon envisions a vibrant set of distribution channels being in place to ensure demand is always met by a doorstep supply. Simon’s ultimate strategy to change the system is not to grow his organization, or even to make his particular anti-diarrhea kit available worldwide, but instead he aims to catalyze uptake of his model’s key principles and learnings—i.e. user-led design, and sustainable local value chains, to get health products effectively distributed and taken up by patients. In the field of childhood diarrhea, his strategy is to demonstrate the effectiveness of his model across Zambia by spreading province by province, establishing the supply chain, kick starting the market and then stepping back. Once a country-wide system is in place, Simon will have fully demonstrated to the international community the effectiveness of his approach on this pervasive problem. Data is also being carefully collected, with influential peer-reviewed studies ready to publish, in order to influence the world of international development, and other ministries of health, so that they too can implement his approach. Simon is currently creating an operations manual and a policy document so that his model can be adapted to meet the needs of different countries around the world, as well as new health challenges. In the long run, he sees his role as an international champion and advisor on doorstep health, public-private partnerships, and sustainable value chains. Already he is working closely with the major international institutions, health experts, and pharmaceutical companies to drive adoption of his learnings.

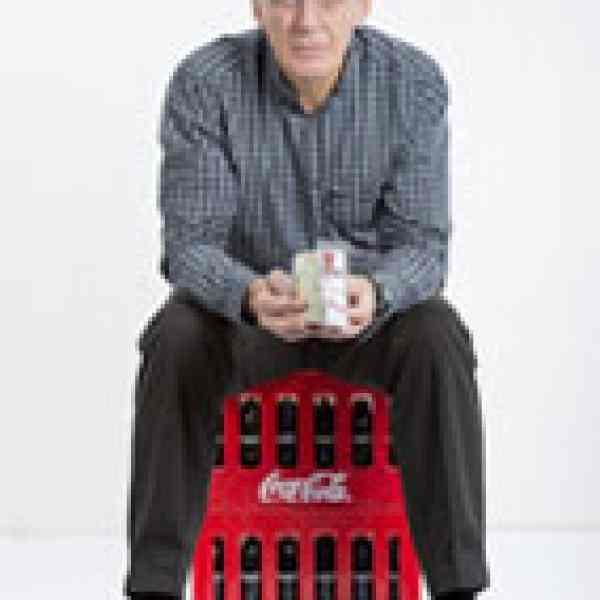

The Person

Simon grew up in rural Wiltshire in the UK where he spent most of his time on the neighboring farm. He studied Agriculture at the University of Reading, and then graduated with an MSc in Tropical Animal Health and Production from Edinburgh University. Simon always had a great interest in development issues. When he was still a student, he moved to Bolivia for a Natural Resources Studentship Scheme that he received from the UK Department for International Development (DfID). His future wife Jane followed a year later and they got married in Bolivia. Jane later became Simon’s partner in setting up ColaLife.

Working for DfID for more than 12 years in several countries in Africa, South America and the Caribbean, Simon became a recognized expert in International Development. However, he consistently questioned the prevalent model of international agencies parachuting in to educate people, set up top-down solutions, or solve problems on their own. In Zambia in the 1980s, for example, Simon was working with the British Aid Programme on a UK-funded integrated development project for rural farming communities. Instead of creating a solution himself, he was part of a team that designed a structure to hand management decisions over to local council officers and decision maker—a first for the Programme, and revolutionary at the time. He has continued to embed participatory approaches and capacity building techniques throughout his entrepreneurial journey. It was in Zambia that the seed for the ColaLife idea was planted. 20 years before launching as a non-profit, Simon had a realization that he could buy a bottle of coke in the most remote places in rural Africa, yet there was no access to lifesaving treatments. He attempted to gain Coca-Cola’s attention, but struggled to influence the right people using the telex machine – the only communication device in rural Zambia at that time.

Simon returned to the UK in 1991 and founded WREN Telecottage, one of the first community-based Internet access centres in the world—which later became an international demonstration centre. In 1995, he became the director of the National Rural Enterprise Centre, a division of the Royal Agricultural Society of England. In 2002, Simon founded another venture, a social enterprise called ruralnet|uk, which utilized internet-based innovations and social media applications to support farmers and residents in the UK’s “last mile.” Before his peers or colleagues, Simon was very quick to see the potential value of “open innovation,” online communications, and social media. He directed the Royal Agricultural Society’s National Rural Enterprise Centre for seven years, and managed Regionet, which piloted the use of IT in public services through collaboration across 9 countries with 34 public, private, and voluntary sector partners. These experiences also persuaded him of the power of “unlikely alliances” in cross-sector collaboration. It is these principles that have informed ColaLife’s model and ethos.

ColaLife first started in 2008 as a Facebook group set up by Simon and his wife Jane, calling big companies like Coca-Cola to take action to alleviate poverty. The core idea was to encourage Coca-Cola to use its distribution channels in developing countries to distribute life-saving medicines. Two years later, the group had 8,000 supporters, but no one had taken action on the ground. At that time, Simon was working as Head of the Third Sector Team of the UK Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), but he quit his secure and prestigious position in order to move to Zambia and make ColaLife a reality.

Simon launched ColaLife’s first pilot trial in December 2011 after getting financial support from DfId, Johnson & Johnson, COMESA, Honda, and Grand Challenges Canada. He also concluded high level strategic partnerships with UNICEF and Coca-Cola, as well as local partnerships with producers, wholesalers and retailers. Simon and his wife designed an innovative solution to fit ORS kits in the Coca-Cola crates that were to be distributed in two remote trial areas in Zambia. The user-friendly design of the kit proved more important than its ability to fit into cola crates. More than 26,000 kits were sold in 12 months, and Simon’s work was internationally acclaimed, winning numerous design, health, innovation, and entrepreneurship awards—Including Ashoka Changemaker’s Global Health Innovation Competition—as well as being featured at the UN General Assembly as a Breakthrough Innovation for Child Health in 2013. Following the first trial, ColaLife and partners have redesigned the ORSZ kit to reduce the price even further while keeping the key user-friendly functions.