Introduction

Juan Jacobo Hernández works to fight the spread of HIV and AIDS among Mexico's homosexuals and bisexuals, who are extremely vulnerable to the disease and do not receive adequate information about their risk from existing government programs.

The New Idea

Review statements from the 1996 international conference on the HIV/AIDS pandemic, held in Vancover, B.C., reported that urban males who have sex with other males are one of two Mexican populations where the disease rates are climbing: the other is a newer epidemic among rural women who are infected through heterosexual contact. Juan Jacobo Hernández addresses a reality behind the statistics: that despite a relatively high proportion of men who have sex with other men, homosexuality is still poorly understood in the region, and few men identify or describe themselves with terms like homosexual or bisexual. It follows that it is difficult to successfully target this audience. Further, Juan believes that the HIV prevention campaigns that do appear on television, which generally focus on abstinence, are not realistic or even intended for the gay population. Juan has developed techniques to effectively inform males who have sex with other males of their risk of contracting the AIDS virus; his work evokes Mexico's success over the 1990's–in large part through a public information campaign–to halt the spread of the disease via contaminated blood. Working on the premise that the homosexual and bisexual populations are not protecting themselves adequately from any sexually transmitted diseases, Juan Jacobo decided to discover the places where they carry out their relations and spread his message to them directly. He found that the most common settings for homosexual activity include the 30 to 40 public bathhouses in Mexico City, so he takes his message there.

The Problem

Since the earliest tracking of HIV and AIDS in Mexico in the early 1980s, the disease has continued to affect homosexual and bisexual men. Eight years after official records began, the incidence of HIV in men who admitted having had sexual relations with other men increased from 390 in 1987 to 7,988 in 1994–an increase of more than 2,000 percent. Though government health reports do not directly refer to a male-to-male sex category, obliquely attributing 51 percent of AIDS cases to an "unknown risk factor," it would seem apparent that a large number of men are secretly engaging in homosexual relations. One of Mexico's most common meeting points for homosexual and bisexual men is the public bathhouse, where clients, bath attendants and masseurs all frequently engage in homosexual activity. Most of them are unaware of the risk of diseases they face and do not know how to protect themselves.

Juan points out that the government has failed to generate concrete proposals and strategies that are geared to highly vulnerable homosexuals and bisexuals, though public health policies have resulted in the dissemination of information to the general population. Even there, the information is limited by social assumptions that people will not engage in sex outside of marriage or for other purposes than procreation, thereby conveying dominant messages of abstinence, fidelity and monogamy and remaining silent about the need for protected sex. Though correct condom usage is just beginning to be promoted on television and in printed materials, it does not reach the same-sex high risk groups because it, too, appears in heterosexual and marriage-oriented contexts.

Since bisexual and homosexual men are not specifically identified as the subject of public health concern, there is no energetic public campaign to find a way to effectively communicate with them about their risk, which remains the highest in Mexico. The task is difficult, as Juan points out: information that is targeted openly to same-sex groups may never succeed in reaching bisexual and homosexual men, who often don't consciously identify themselves with the gay culture or lifestyle.

The Strategy

Juan determined that it is strategically necessary to deal directly with homosexual activity and not only with the segment of the population that openly calls itself gay. He has trained a cadre of volunteers to act as "prevention squads" who confront the same-sex population where it lives. Juan chose to begin his prevention project in the public bathhouses in Mexico City because (1) they are sites attended by a great number of men where impersonal sexual relations occur; (2) both homosexuals and bisexuals use them; (3) there are nearly 30 bathhouses in the metropolitan area, attended by between 2,000 and 2,500 men daily; (4) approximately half of the attendees have a female partner who is also at risk; (5) the masseurs and bath attendants generally participate in the unprotected relations; and (6) people known to be HIV-positive have been discovered attending the bathhouses, which confirms their danger as active focus points for new infections.

Juan sends his prevention squads to the bathhouses to mingle among the clients and spread his message of disease prevention. He specifically targets the bath attendants and masseurs to teach them about the dangers of unprotected sex; how to detect visible signs of sexually-transmitted diseases, which enhance vulnerability to HIV; and the importance of correct condom use and other preventive methods. Juan also disseminates information about HIV and encourages the men to be tested for the disease. A major plank of his strategy is to prevent further transmission of AIDS by secret bisexuals to their female partners. Ultimately he counts on the motivation of savvy bath attendants, who often know their clients and care about them, to continue to be educators of the clients well after the prevention squad has left.

Juan also targets "dark room parties," additional meeting points for gay men. If the participants refuse to listen to his message, he threatens to call the tax collectors and health department. He is determined to do what it takes to make them listen.

When he began, Juan limited his work to three bathhouses in the Federal District in order to observe the responses and refine his methodology over the course of the first year. Since then, he has begun to expand his work in the city. In the long term, Juan hopes to duplicate his method of taking his message directly to the gay population in bathhouses and other settings all across the country.

The Person

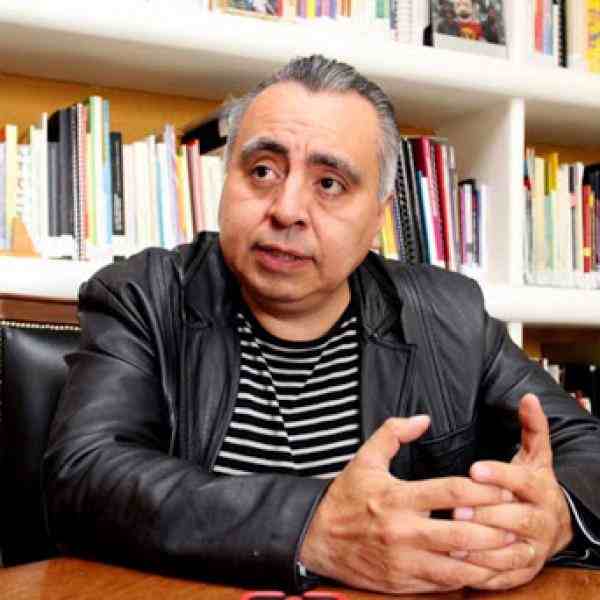

In early childhood, Juan became aware of his homosexuality, and he searched intensely for a place to be accepted. First, he turned to the Catholic Church. He became president of the Christian Student Movement, where he learned respect and tolerance. Later, in the Anglican Church, he discovered the importance of work and the true potential of an organization. He participated in the student movement of 1968, in a teachers' union and in the Mexican Homosexual Liberation Front, where he learned new ways of confronting and discussing issues relating to homosexuality. Finally, starting in 1981, he became part of an effort to build a movement for liberating homosexuals. This step coincided with the eruption of AIDS in Mexico (1983), and he has worked in the fight to prevent AIDS ever since.

Juan's life was scarred by the death of his partner, Mario. This event led him to take action to protect his own life and the lives of others close to him by spreading information and preventing HIV/AIDS. In 1983, he founded Colectivo Sol, a nongovernmental organization in defense of homosexuals' rights. Since then, he has been active on a national level in the areas of education and AIDS prevention and in providing information to people with HIV.