Introduction

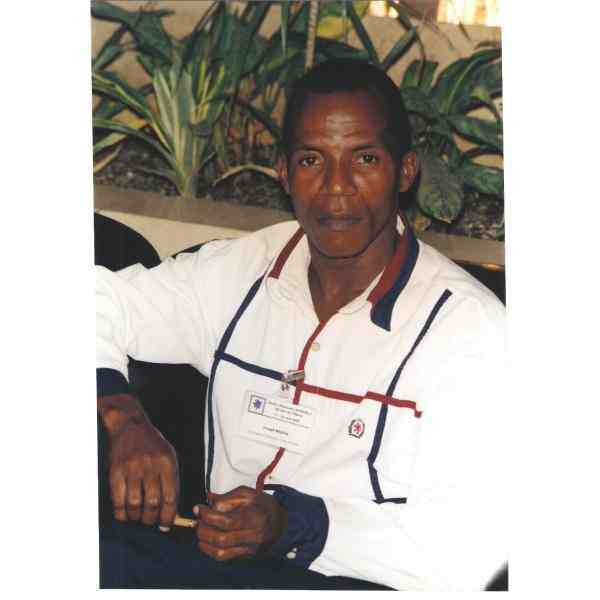

Working in the poorer sections of Cote d'Ivoire's capital, Abidjan, that are not served by public trash collection services, Joseph N'Gata has pioneered a cost-effective youth-based model for municipal trash collection.

The New Idea

Joseph N'Gata has found a simple, economically sustainable solution to the problem of garbage collection in underserved neighborhoods in Abidjan that simultaneously provides a formative "first job" for unemployed youth.Working in poor neighborhoods that lack city services, he employs teams of local young people who go house to house collecting garbage for a small fee and taking it to special drop-off points where city services transport it to official dumps. He is now bringing his system to other neighborhoods and working closely with municipal authorities to show them how this inexpensive and efficient system can work in their areas.

The Problem

Abidjan, like many African capitals, has witnessed rapid, unplanned growth as people from the countryside stream into the city in search of a better life. From 1950 to 1990, Abidjan's population grew thirtyfold, from 70,000 to 2.1 million. Consequently, poor neighborhoods have sprung up in a chaotic sprawl on all sides of the city.

The narrow, unpaved roads in these neighborhoods make it impossible for the large city garbage collection trucks to remove residents' garbage. Residents live in appallingly unhealthy conditions as trash piles up in the streets and informal dumps are created next to houses and schools. Even if the logistical problems of getting trucks in and out of poor neighborhoods could be solved, municipal authorities lack the capacity and resources to provide services to all residents.

The conventional prescription of privatization has been tried in Abidjan, with only marginal success. ASH, the private company that won the government contract to collect Abidjan's garbage, is currently only able to cover between 50 and 60 percent of its concession.

Whether public or privatized, when sanitation services are not stretched to cover the entire city, it is the poorer neighborhoods that are neglected.

The Strategy

Joseph's strategy is disarmingly simple. He begins in a neighborhood by clearing away the major piles of trash that have accumulated in informal dumps. He and his workers do this initial clearing for free as a gesture of goodwill to the community and to demonstrate their competence and commitment. Next, Joseph and his team go house to house, explaining their service and the costs involved. During this initial phase, they spend many hours educating the community about the health hazards of uncollected trash in the neighborhood.

Each family that subscribes to the service is entered into a ledger, and a special mark is painted on their trash can and the front of their house to indicate that they are subscribers. Families pay the equivalent of between 20 and 80 U.S. cents per month to have their trash picked up five or six times a week.

The collectors come directly into people's courtyards to pick up their garbage. Before disposal, the trash is sorted and valuable glass and plastic are separated and sold for recycling. Collectors are paid according to how large a cart they are able to use and how far they must travel to the local drop-off point. A typical salary for a collector is $30 to $40 per month, basic income for youth in the community. A financial controller is assigned to each zone to manage client payments, keep records, recruit collectors and solicit new clients.

When he founded his company, the Ivoirien Assistance Society, in October 1990, it employed four people and one cart. Joseph now employs 24 full-time workers who use nineteen carts and a tractor to collect approximately 246 cubic meters of garbage each day.

Joseph runs a tight ship that has become an important resource to, and model for, the communities in which it operates. He is adamant that "there can be no bosses sitting around in an office with this kind of work." In succeeding where many others have failed, he has kept administrative and personnel costs to a minumum. Joseph himself regularly makes the rounds of the neighborhoods covered by his service, observing his work crews and talking to customers. He has also improved the design of the garbage carts used by his collectors. The new four-wheel design allows collectors to haul much greater volumes of trash on each trip. Joseph also keeps scrupulous records of the amount of trash collected, the fees collected and the percentage of the population subscribing to his service.

Workers are recruited with care, using a one-month trial period. In their turn, community youth have come to see the Society as a rare opportunity for that elusive "first job."

Key to the sustainability and expansion of his project is the fact that Joseph works closely with municipal authorities and skillfully manages these often delicate relationships. Since these authorities are responsible for all trash collection in their areas (though none are able to provide 100 percent coverage), private trash collection is a politically sensitive issue. Residents believe that the mayor's office should provide free trash pickup; they are sometimes resentful when asked by Joseph to pay. Mayors are worried that an effective private service will point out their own shortcomings. Therefore Joseph cooperates with local public sanitation departments to coordinate his activities with the trash collection services that the city government is able to provide. At the same time he has been able to convince local residents of his good intentions and the fact that efficient trash pickup that costs 60 cents per month is better than free collection that does not happen.

Joseph is steadily expanding the society throughout underserved areas of Abidjan and to other cities. He has begun to train other groups in his method. In Dukou, a small town near Abidjan, he trained a group of young people in his method and met with the mayor to explain how such a project could complement the municipal trash services. Joseph has also spoken to groups of mayors at several conferences, including a 1994 gathering entitled "The Privatization of Municipal Services and Participation of Local Populations." Over the long term, Joseph believes it is likely that groups like his will be able to purchase large garbage trucks and take over the entire municipal trash collection process.

The Person

Joseph, one of nine children, was born in a village 100 km north of Abidjan. His parents were poor farmers who grew coffee and cacao. Joseph attended a Catholic primary school in the village and left at age 14 to attend secondary school in Abidjan. He put himself through secondary school by holding down odd jobs after school hours and returning to the village to help his parents during vacations.

After he graduated from secondary school in 1987, he began tutoring children privately. Later that year, he landed a teaching job at a private school in Abobo, the section of Abidjan where the society is based. For some years he cleaned the bathrooms at the school where he taught, theorizing that a clean environment will help students take pride in their school and their studies. Although Joseph is at a loss to explain why, he has always been extremely interested in cleanliness, believing that a clean living environment leads to greater self-esteem. Frustrated by a large illegal dump next to his house, in 1990 Joseph decided to take action by creating a local group to deal with the problem. After posting notices for workers around the neighborhood, he created a working assistance society. He has now left his teaching job to devote himself full-time to his vision for youth-based public sanitiation services.