Introduction

Sean Sherman helps Indigenous chefs, farmers, and environmentalists revive and popularize “pre-contact” cuisine as a way to tell a different, more accurate story about the Indigenous people of North America. He then harnesses all the interest and opportunities created to systematically improve food systems in tribal communities and beyond.

The New Idea

It is too common for the average non-native American to think of indigenous people as part of the past, and not present or relevant in the United States today. Sean insists that we can get this conversation unstuck – as well as surface solutions for contemporary challenges – by tapping into the power of food to connect. Through restaurants, food trucks, cookbooks, and now a non-profit Indigenous Food Lab and media center hosting apprentice chefs and food systems workers from across Indian Country, Sean is popularizing indigenous cuisine among people of all walks of life.

As important, he is improving food delivery systems that serve tribal communities so that every tribal community in North America will have at least one access point for healthy, local, culturally-appropriate indigenous food. More demand for indigenous cuisine translates into more seed saving, wild harvesting, land and game management, and cultivation of environmentally compatible indigenous plants. In this way, Sean is investing in regenerative economic and environmental practices that protect biodiversity and keep alive a global knowledge base essential for our current environmental challenges and for future generations.

Through all of this, Sean is centering the leadership and agency of indigenous leaders as ambassadors of indigenous cultures, food systems, and environmental stewardship strategies.

The Problem

For more than 20,000 years, people in North America developed rich cultures and local food traditions in sync with natural ecosystems. Yet today, human life on this continent is out of balance with the natural world and we are suffering the consequences, from environmental degradation to poor human health.

To understand how we got here, Sean says, we must reckon with the history of genocide of the people indigenous to North American starting in the 1600s and continuing with the assimilation attempts of the 1800s into more recent times. Over these last few hundred years, indigenous people of the Americas and many of their cultural, legal, spiritual, and food traditions were pushed to the margins to make way for settler colonists and their imported ways of life: innovations like the reservation system for tribal communities; private land ownership for whites; family farms; and a diet rich in meat, dairy, and, later, processed foods.

In the grand scheme of things, these are all recent experiments for North America, and many are not working out. The reservation system is a “perfect example,” as Sean puts it, “of modern-day segregation and manufactured poverty.” The current American diet – in tribal communities and in general – consists heavily of animal products, and the way in which most meat and dairy is raised strains our continent’s life support systems by polluting local water, degrading soil, and producing global greenhouse gas emissions.

Sean believes that we need a different story, one rooted in history that lifts up time-tested solutions indigenous to this part of the world. He believes that food can be both a catalyst for bringing more people into this new, true story, and also a practical part of the solution to the problems we’ve created.

The Strategy

Sean believes that “understanding food helps us understand people who may be different from us.” This has indeed been his own experience, first of mastering European cooking, then reclaiming his family’s own dormant Oglala Lakota food traditions, and then finding power in inviting more people to return to and revive North American food traditions. Through this journey, Sean discovered that exploring Native foods is the most accessible and inviting way for Americans of all backgrounds to enter this different story in a different way. “It has given me—and can give all of us—a deeper understanding of the land we stand on.” And of its history.

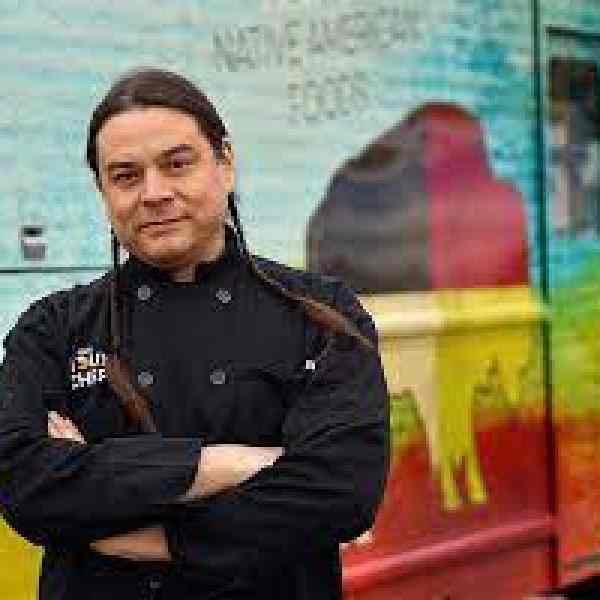

Sean has personally experienced this transformation as a chef promoting pre-contact indigenous cuisine. He’s run a catering business called “The Sioux Chef” and a popular food truck and authored a cookbook that won a James Beard Award. And through this his vision expanded – to ensure that more indigenous chefs, botanists, farmers, hunters, and seed savers transform and restore the tribal communities. To this end, he launched NATIFS (North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems) to ensure indigenous people and tribal communities across North America can develop satellite indigenous kitchens and make healthy, enlivening indigenous foods accessible in their own home communities, while also engaging the wider American public in conversations about history and culture over food.

At the core of NATIFS’ current efforts is The Indigenous Food Lab. It is a professional kitchen and training center for Indigenous food research, education, preparation, and service. According to Sean, “the lab shares ancestral wisdom and skills such as plant identification, gathering, cultivation and preparation of Indigenous ingredients” with the goal of eventually replicating this model across North America, “as a way to empower Indigenous food businesses, because we believe that food is at the heart of cultural reclamation.”

The Indigenous Food Lab’s physical space in Minneapolis, MN, includes a working community kitchen staffed by apprenticing chefs from tribal communities from the Twin Cities and across the region. This kitchen produces hundreds of meals a day and is a significant buyer of ingredients from indigenous producers. Their on-site market plus growing numbers of chefs and home-cooks only drives more demand for Native growers producing heirloom beans, squash and pumpkins, and Native corn varieties and sourcing things like morels, ramps, wild ginger, chokecherries, crab apples, maple, wild rice, and cedar. And last but certainly not least, in 2022 NATIFS launched Owamni, the flagship Indigenous restaurant on the banks of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis that became the winner of that year’s James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant in the United States.

For tribal communities that have become very successful through legalized gambling and other enterprises, NATIFS focuses on culinary programming, training, and education to help them transform their menus and culinary offerings, for guests and their workforces alike. Here Sean points out that, “tribes have the unique opportunity to design their own rules on where food comes from and we can help with that, but it’s an educational issue and these tribes with so much financial resources are great role models for truly implementing these programs."

For tribal communities that are more remote and that experience food insecurity and access issues, NATIFS works directly with them to develop their own Indigenous culinary programming - from designing culturally appropriate menus to running a successful kitchen dedicated to creating healthy Indigenous foods – as well as ordering, processing, storing, and serving food in a way that is both safe and respectful of cultural traditions. The goal is for these communities to recover systemically inter-linked cultural assets and economies: a decolonized righting of relationships with the natural world, scores of dignified jobs in diverse regional foodsheds, a retooling of food systems serving tribal communities, and a strong signal that indigenous communities can and should be engaged as experts in natural resource and land management of their ancestral lands.

Sean and his team will be launching an Indigenous Food Lab in Bozeman, Montana in 2023 with expansion to Alaska, Hawaii, New Mexico, and South Dakota to follow.

The Person

Sean Sherman (Oglala Lakota) grew up in the poorest county with the lowest life expectancy in the United States, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. “When I was 13, I started working at The Sluice restaurant in Spearfish, South Dakota, and I worked in restaurants throughout my teens and 20s. I got my first executive chef job, at a tapas restaurant in Minneapolis, when I was 27.” Around this time, it occurred to him that he had become an expert in European cuisine but had not taken time to understand his own food traditions. This realization set him on a decades-long quest to study indigenous farming, wild food, stewardship, and culinary histories. In 2014 he started a catering business called “The Sioux Chef” and, in 2015, the “Tatanka Truck” in partnership with Minneapolis area non-profits and tribal groups to share food from his Dakota background and using local, indigenous ingredients. In 2018 he won a James Beard Award for his cookbook, “The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen,” and in 2019 was recognized with the James Beard Leadership Award for his efforts toward the “revitalization and awareness of indigenous food systems in a modern culinary context.”

Sean is clearly motivated by a sense of urgency and history. So much has changed so relatively recently. He’s shared that,

"My great grandfather helped fight off General Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn [in 1876], alongside other Lakota and Cheyenne, not even 100 years before my birth. I think about my great grandfather’s lifetime, being born in the 1850s—toward the end of the genocides that began in the 1600s across America and stretching into the subtler but still damaging years of assimilation efforts we have endured since. He saw escalating conflicts between Lakota life as he knew it and the ever-emerging immigrants from the east. He witnessed the disappearance of the bison, the loss of the sacred Black Hills, the many broken promises made by the U.S., along with atrocities like the Sand Creek and Wounded Knee Massacres. He saw his children attend the boarding schools where they had their hair forcibly cut and were punished for speaking their languages."

If he were alive today, Sean’s great grandfather would see a glimmer of hope: despite several generations of attempts to wipe out tribal communities and their cultures, his great grandson is helping usher in a reckoning with this history and a revival of food and wellness traditions that have sustained humans on this land for hundreds of generations.