Introdução

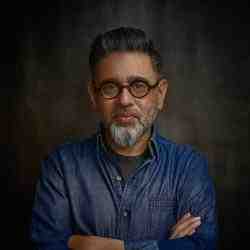

Sergio Marques Santana, 32, is improving the lives of the low income population of the Baixada Fluminense, a proletarian suburb of Rio de Janeiro and of poor rural groups by developing concrete opportunities of exchange and support among these two groups.

A nova ideia

The neat white buildings lined with ornamental greenery stand out in a neighborhood of mud streets and ramshackle housing, but the buildings house an enterprise that is very much a part of this poor community on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. This is APAC, the Association of Autonomous Producers of the City and Countryside, where 30 machinists and metalworkers produce low-cost farm implements and sanitation equipment and, more recently, 18 women sew uniforms and other special order clothing, sometimes at cost. They are not employees. They built the shop and office complex themselves and are co-owners who administer their enterprises through consensus. "It's really a revolution in labor, isn't it?" asked a member of the sewing cooperative.

Sergio Marques Santana co-founded, coordinates and presides over APAC, but he invariably says "we" rather than "I" when speaking of his work there. His highly democratic entrepreneurial concepts have developed over 15 years of teaching community based courses in trade skills and have evolved into APAC, inaugurated in July1987. Santana and associates travel to rural areas throughout Brazil showing samples of the small farm equipment they produce and listening to farmers' ideas on tailoring tools to their area's topography and climate. APAC associates return and build custom manual and horse drawn farm implements and sell them at low cost mostly through rural unions and cooperatives. APAC averaged ten sets of plows and accessories a month in 1989 in addition to other orders. As elsewhere, subsistence and truck farms in Brazil are fast being replaced by large-scale farming suited to export crops and promoted in agro industry. At the same time, cities have swelled partly with migrants driven from rural areas in search of jobs. The Baixada, or lowlands of Greater Rio, where Santana lives and works, exhibits the disastrous consequences of 30 years of rural to urban migration: nearly four million people living in precarious conditions and largely depending on low paying jobs far from their homes.

With startup money from the Lutheran Church's Bread for the World Program, Brazil's national development bank and other lenders and donors, APAC built and equipped the machine and metal shops. It no longer receives outside funding yet has reached a self-sufficiency that allows associates to stay close to home, enjoy autonomy and still earn five times more than they would earn in industrial jobs hours away by crowded bus. One of Santana's dreams, he says, is a lasting structure, an exchange among small scale producers that frees them from the dictates of big industry and big agriculture." From a commercial point of view, it's complicated for a small producer to manage financial stability," he says. "The only way we know to make it happen is to create a network of exchanging what's produced here in the city and needed in the country for what's produced there and needed here." APAC has bartered equipment for food within Rio de Janeiro state, brought farmers to see the metal and machine shops and taken shop associates to see the farmers' work. Farmers have seen their cotton made into uniforms at the sewing cooperative, and machinists have seen their plows working fields. So the space diminishes between city and country, producer and consumer.

Santana's other dream for APAC is seeing it raise the awareness and the living standards in its own neighborhood. "People see a thousand pieces of equipment leaving here and it means nothing to them. It might benefit them in the long run, but they don't perceive any difference because of APAC being here," Santana says. "We have problems here, very serious health problems, infectious diseases, high infant mortality, filth. All this work we're doing with the city has one objective, to construct a garbage treatment plant. "In addition to farm equipment, APAC builds sanitation equipment for the government of Sao Joao de Meriti, a municipality of 700,000 people within Baixada. "Sanitation now is a total disgrace," says Santana. "We calculate that this city produces 350 tons of garbage a day. I don't really know where it goes, but I do know that one fourth of it is not collected at all and just piles up on street corners and in yards, generating rats and insects and disease. "APAC associates are studying recycling and visiting efficient garbage treatment plants when they travel. They already manufacture all the equipment needed to make concrete drainpipe, and the city is asking APAC to take over its drainpipe plant, an offer the association is considering. To get the sanitation equipment contract, APAC overcame pressures from cartels accustomed to bribing politicians and padding bills on public contracts. Santana says APAC has surprised city officials by filling orders on time and within budget. The pressures have stopped now that APAC has established that its associates genuinely intend to help upgrade living conditions in their city. For Santana, one of the most touching moments in APAC's growth was the facility's inauguration, when even pouring rain and ankle-deep mud did not keep area residents away. They came to see what APAC was about, Santana says, and their interest and participation have grown ever since.

O problema

The Baixada Fluminense is subject to chronic unemployment, high crime rates and poor health services. The people of the region serve as a large pool of labor (especially iron workers) for the employers of Rio de Janeiro, swelling the city every day to work in the lowest paid jobs, traveling 2-3 hours in crowded buses to reach the city. Eighty percent of the rural population are small farmers who live without the most basic of necessities. These small producers cannot afford farm equipment that is technologically sophisticated and expensive. Many of them leave the countryside and become urban workers.

A estratégia

1.Santana, through APAC, works to build ties among rural and urban small producers to their mutual benefit. Manufacture of small farm equipment offers Baixada residents an alternative to working long hours far from home for a minimum wage. The equipment is affordable for subsistence farmers, especially when purchased and used collectively, and is custom-built, when necessary, to soil and topography to boost crop output.2.Workers within the Baixada collaborate on alternative services and equipment useful in the low income periphery, such as direct supply of farm goods, community repair shops and garbage recycling and treatment.3.Participants share experiences and spread ideas through popular movements, community groups and institutions in the Baixada, in rural areas and in cities throughout Brazil.

A pessoa

Santana is from Brazil's poor Northeast region and grew up in the Baixada. He began working at age 12 and, like most workers there, made the tiring daily trips to work in the city. In the 1970s, Santana became involved in the progressive Catholic Church's social work and left a teaching job at a private school to coordinate adult education at a church related alternative learning center. From that point, involvement with labor struggles, residents' associations and job training activities "did the rest" he says when asked what motivated him to undertake this project, Santana answered, "It was the feeling that all men have equal rights to respect and dignity."