Introdução

Based on his experience as a penitentiary system inmate, Ronaldo Monteiro is transforming how society views convicts. By constructing support networks and promoting entrepreneurialism, he is proving that ex-prisoners can be productive members of society and can break the cycle of repeat-offending.

A nova ideia

Ronaldo’s citizen organization (CO), the Incubator of Ex-Prisoners’ Enterprises (IEE), reintegrates former prisoners into society as productive citizens. Without the services to prepare prisoners to leave prison and the societal stigmas against convicts makes it difficult for ex-offenders to restart their lives. Ronaldo identifies and develops entrepreneurialism among prisoners and provides emotional support to them before and after they leave prison. This transitional approach enables inmates to plan to re-enter society and provides them with the autonomy and confidence to reconstruct their lives. Through the Center of Social and Cultural Integration (CISC), Ronaldo mobilizes actors from the public and private sector to help foster entrepreneurial skills among prisoners while they are incarcerated. Since it is often extremely difficult for them to reintegrate into society and find employment after leaving prison, CISC builds strong social networks and nurtures skill sets while prisoners are serving time. When they are released they have a relationship with CISC and can find empowering job opportunities quickly. For ex-offenders who do not start businesses, CISC offers social support and provides job opportunities in the enterprises of other ex-offenders. Ronaldo is expanding this support network throughout Brazil.

O problema

The intense growth of violence and criminality in Brazilian society has ranked it number four worldwide with the number of homicides per person. Societal pressure for a response from the State has resulted in a considerable increase in the prison population—the majority of prisoners being poor, black (about 85 percent), and young. Between 2003 and 2006 this population increased from 308,000 to 406,000 with no corresponding increase in prison capacity. As a result, the country has an overcrowded system with more than 60 percent of prison establishments in precarious condition. With a focus solely on incarceration, concern for the imprisoned and their rehabilitation and reinsertion into society has been abandoned.Without the minimum conditions for human dignity, the prisons constitute an unhealthy environment with poor food, a proliferation of illnesses, and an absence of necessary psychosocial services. In addition, the dominance of criminal organizations within prisons creates a perverse logic which keeps the relatives of prisoners away and reinforces the characteristics which led to imprisonment. In this situation, patterns of behavior incompatible with reintegration emerge, and take away an individuals capacity to envision dignified alternatives outside of the prison. Therefore, instead of creating channels of resocialization, the penitentiary system perpetuates an eventual return to criminal life. Though international organizations have denounced these violations of human rights the State action has been fragmented and inefficient. With a concentration on the repression of crime, the sparse programs for prisoner rehabilitation have been incapable to achieve concrete results. Most of these programs consist of training courses and professionalization workshops to make prisoners able to access the job market. Others, constructed in partnership with the private sector, aim to produce goods inside the prison, utilizing the public infrastructure and cheap labor.These programs consistently fail due to their lack of structure and the necessary channels for effective assimilation of ex-offenders into the job market. Neither the State nor the companies that produce goods in prisons, incorporate these persons when they leave. Moreover, in an economy where opportunities are scarce, persons with criminal records, lack of formal education, and are black, will have little chance to find employment. Thus, without alternatives for a life outside of prison, returning to crime becomes the principle, and often, the only alternative in the months after release. Although there is no official data, it is estimated that the national rate of repeat offence affects 70 percent of ex-offenders. Though returning to the work market has been identified as a key element to assure reconstruction of a dignified life for the ex-prisoner, only 2 percent of the 500 largest companies in Brazil offer employment opportunities to ex-offenders (Ethos Institute). This explicit discrimination demonstrates the necessity for concrete initiatives. Another alternative towards employment is the development of entrepreneurial pursuits; though there is no public policy or COs promoting the creation of enterprises based on the special conditions of the ex-offender. To develop an enterprise, the ex-prisoner faces diverse factors including, a lack of knowledge, lack of inclination towards entrepreneurialism, lack of support from family members, and an absence of resources and access to lines of credit. Therefore, the chance of succeeding with a micro or small enterprise is low. According to SEBRAE between 30 and 60 percent of companies created fail in their first year. The growth of business incubators has had positive results in this field—some have been able to increase the survival rate of enterprises up to 80 percent.

A estratégia

To break a cycle of incarceration in which prisoners are released and reimprisoned, Ronaldo created IEE to business entrepreneurialism among ex-prisoners. The CISC fills the social needs of IEE and builds self-esteem and social networks.The Incubator program has two phases for ex-offenders: First they undergo pre-incubation to deal with technical and theoretical training for management. Later in the second phase, known as incubation, they deepen their conceptual understanding of enterprise for success. The most important factor in the success of this model is the time it takes to initiate the business. Since ex-prisoners vulnerability may be very high, Ronaldo employs two strategies: Paying a grant and benefits to every person in the Incubator and accelerating the process of pre-incubation which permits the ex-offenders to quickly generate an income and sustain themselves—to prevent repeat offense. To increase collaboration among prisoner-run enterprises and businesses, Ronaldo is constantly building the IEE network. Understanding the importance of a social network for the imprisoned, Ronaldo involves the family as a way to strengthen familial ties and stimulate the construction of a law abiding life out of prison. Soon after his release from prison, Ronaldo created healthy spaces and play activities for the families of prisoners during visiting days and CISC continues to implement this strategy. It was during this work that Ronaldo saw the necessity to establish projects inside the prisons to overcome prisoner passivity and dependence; getting them to construct their life. Stimulating their entrepreneurial skills achieved this autonomy, benefitting not only the prisoner, but the prison, and eventually the private sector.Through collaboration with the government and other COs, CISC created centers of production in prisons where each prisoner makes a product instead of producing goods made by several people on an assembly line. This enables ownership of work, creativity and production. To guarantee compensation of their work, Ronaldo negotiates the distribution channels with private companies and the government. For ex-offenders who do not start a business, IEE finds jobs with businesses run by former inmates. In this way, a network of support is developed with ex-prisoners helping other ex-prisoners. Ronaldo also formalizes this support through a Network of Support to Ex-Offenders, an initiative that brings together ten COs that make diverse services available.IEE is countering social stigmas by proving that ex-offenders can be positive economic and social forces in the community. Ronaldo is negotiating a microfinance program with the Federal Savings Bank that will offer microcredit to IEE businesses. IEE currently operates in six states offering technical and theoretical support for starting sustainable business ventures. In 2008 Ronaldo expanded IEE to three more states, with his goal being to make IEE a national program. Ronaldo is also negotiating with private investors and the government about adopting IEE’s model as national policy for prison reform and prisoner empowerment.

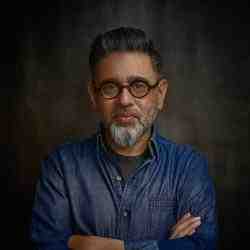

A pessoa

Ronaldo was born into a lower-middle class family in Niteroi and had the opportunity to study in private schools and at the Rodrigo Lages Technical School. As one of the few black students, Ronaldo had difficulty socializing until he excelled in sports—this opened a path to social recognition. Although he had an interest in writing and music, his father’s strong influence led him to enter the Army where he trained as a parachutist. In 1979 he entered the Faculty of Physical Education at UERJ, but was left unable to do his studies and work in the Army. Ronaldo married in 1981 and with three children, he began to frequent the growing number of racketeering and nightclubs—influenced by friends and his father. While still an official in the Army he became involved with organized crime, and was responsible for planning and execution of various kidnappings in Rio de Janeiro. Due to misconduct, after ten years in the armed forces, Ronaldo was expelled. In 1991, he was sentenced to twenty-eight years in prison for kidnapping with intention to extort.Rejected by his family and friends who had thought him as an exemplary professional, Ronaldo served thirteen years of his sentence and passed through six prison units. The suffering he experienced as a result of the absence of his family caused him to reflect. His dedication to literature and religion helped him to overcome the loneliness and guilt and allowed him to initiate a process of transformation as a person.During “visiting days” in the prison, Ronaldo noticed the prisoners’ difficulties relating to their families, especially with their children—abandoned in storehouses while the prisoners had conjugal visits with their wives. Because of this, Ronaldo started to bring the children together and organize educational, cultural, and leisure activities, creating the Child Project. He gained the support and respect of the prisoners, the social assistance department of the prison, and even the support of someone he had kidnapped, a member of the Association of Businessmen of Complete Gospel (ADHONEP). With his religious ties, Ronaldo assumed the role of an ecumenical leader, and claimed freedom for all religious worship. He gained credibility and the participation of detainees of various faiths, in all the initiatives he led. The success achieved by the initiative was noted by the government, which decided to replicate the project in other prisons; transforming it into public policy, without however, recognizing Ronaldo as the leader of the program.His continuous search for solutions for the prisoners led him to promote familial integration and income generation, organized through workshops during and outside visiting hours. Ronaldo created the Paper Workshop, a project in which prisoners are paid to produce paper and recycled products—and replicated in six states. For these initiatives, Ronaldo was elected as President of the Mandela Institute, the first assistance institution for detainees in the prison system, created in 1989 in Lemos Brito Prison.In 1999 Ronaldo became a student and then an educator for the Committee for the Democratization of Information Technology—pushing for digital inclusion in prisons. This contact confirmed for him the necessity to also work with integrating ex-offenders back into society and identify employment as the principle challenge to do so. In 2001, while still in prison, he created the project One Chance, to prepare prisoners for the job market and to promote resocialization through entrepreneurialism. In 2003 this project became the CISC–Uma Chance, a CO with a mission to promote innovative solutions in economic development and the social inclusion of men and women ex-offenders of the penitentiary system. In 2006 IEE was launched.