Introduction

By training human rights organizations to use the monitoring and enforcement procedures made possible by the African Charter, Ashoka Fellow Alpha Fall and Julia increase the influence and efficacy of international human rights law.

The New Idea

Alpha and Julia teach African organizations to use the procedures for monitoring and enforcing human rights established in the African Charter and embodied in the African Commission. In the past, only a few specialized lawyers had such skill; Alpha and Julia are sharing their expertise so that human rights activists can use the Charter for legal recourse. Alpha's and Julia's objective is to make procedures more transparent, apply them to specific cases and minimize some of the obstacles which for non-lawyers might otherwise be insurmountable. They plan to train those organizations so that they will no longer require the Institute's expertise in order to prepare lawsuits and start actions on their own at a national and a pan-African level.

The Problem

In Africa and throughout the world, international human rights law creates opportunities for social advocacy. In principle, a human rights treaty is a forceful instrument that reaches down from international agreement to national application. However, international human rights law has not yet reached its potential because it has been largely a specialist's discipline, even among lawyers, and it is difficult to enforce.

In the Americas, an NGO specializes in litigation before the Inter-American Court and Commission, allowing regional human rights mechanisms to be used more frequently and effectively. Supplied with local evidence, this organization brought ground-breaking cases that not only provided remedies for individual victims, but also set important precedents in international law and changed state policy.

The most prominent example of human rights treaty law in Africa, the African Charter on Human and People's Rights, was adopted by the pan-African Organization of African Unity in 1981 and went into force in 1986. It has now been ratified by 54 countries in Africa, an impressive demonstration of apparent consensus. The Charter creates an African Commission as a monitoring and enforcement body with broad powers. In extreme instances of non-cooperation, Africans can use treaty law to sue their government. In this way, international law serves as referee in a relationship that may turn oppressive.

Fewer than 10 people in and outside Africa have the expertise to present cases to the Commission. Most represent prominent Western human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, Interrights, and Human Rights Watch. A few African individuals and organizations, mostly Nigerian, have this ability.

The Strategy

Alpha's and Julia's organization, the African Institute for Human Rights and Development will combine the success of African human rights organizations in publicizing human rights with the distinctive Inter-American practice of impact litigation that brought ground-breaking cases and precedents in Latin America.

They established the Institute because they believe that the Organization of African Unity (OAU) has potentially powerful treaty law, most of which is unknown and goes unused. While working in the legal section of the Secretariat of the African Commission, Julia and Alpha came by the rather arcane, detailed knowledge of the Commission's procedures, and saw how in a few cases the Commission's actions saved and changed the lives of African citizens.

Existing cooperation between the African Commission and civil society created a constituency keen to gain the expertise that Julia and Alpha identified. Informally, they started to pass along suggestions and knowledge of the Commission's potential and procedures. The great number of inquiries led them to create the Institute for Human Rights and Development in May 1997.

Among the Institute's programs is an effort to train individuals from NGOs in the procedures of the African regional system. A second program is litigation, which will take specific cases to the African Commission. The Institute shares its institutional resources and expertise, while participants bring their extensive experience with actual problems and ideas for solutions. Supporting these two programs are research and publication, which will make essential information available for training, and provide the theoretical background for litigation.

NGOs from more than 12 countries participated in the Institute's training and went step-by-step through the research, legal grounding, preparation and submission of their cases to the African Commission. There is a follow-up in the following five years and the participants can call upon the Institute's resources whenever need be.

Their overall objective is to raise the number of African experts who will be able to take action at the national level but also in front of the African Commission. To increase their effectiveness, those experts will hold training sessions in order to build the capacities of other grassroots organizations.

The Institute and the NGOs always remain mindful that they are partners of the African Commission as well as of one another. Therefore, even for litigation cases, Julia and Alpha build up constructive rather than confrontational relationships with the African states and African Commission, and they train other NGOs to do the same.

The Institute is looking forward to establishing good precedents in international law and changing national policies, but it also seeks concrete resolution of the cases it handles– resolutions that will be visible and felt by the citizens themselves.

One future strategy, said Julia and Alpha, will be to build relations with other parts of the citizen sector. They want to show more small African development organizations how to incorporate economic, social and cultural rights into their outlook and programs.

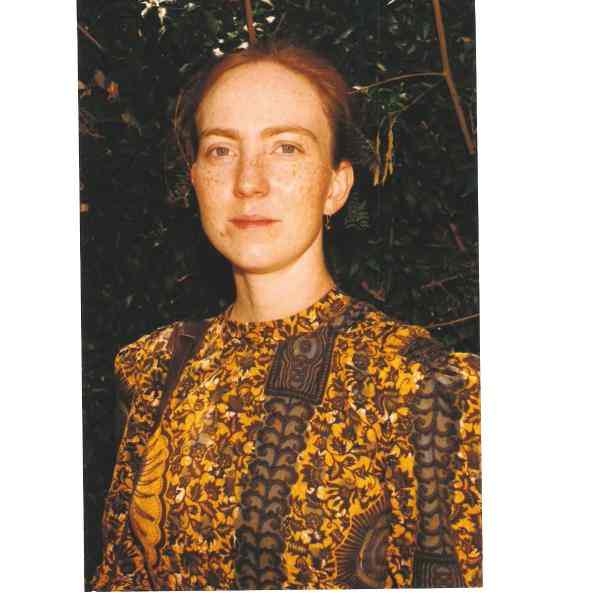

The Person

Both Julia and Alpha were raised to believe in values such as dignity, respect and equality for all human beings regardless of religion, race and nationality.

Julia grew up in the United States. In secondary school, she was on the founding board of a youth organization working on community construction projects in Washington. Alpha started working in human rights when he was a student: he is one of the founding members of a major human rights organization in Senegal.

Julia also volunteered in prisons and at university studied the Northern Ireland conflict. There, she realized that the failure to respect human rights accentuated the alienation that individuals felt from their government, and worsened the conflict. From a young age, Alpha decided to be a human rights professional–even after working for a renowned law firm in Dakar. While studying law at the University of Dakar in the late 1980s, he created an informal early warning system to protect women against domestic violence.

After Alpha graduated from University Cheikh Anta Diop and Julia graduated from Harvard Law School in the mid 1990s, they both turned down job offers in law firms. Julia did an internship at the legal section of the African Commission on Human and People's Rights, where she met Alpha. They left the Commission together to create the Institute for Human Rights and Development in 1997.