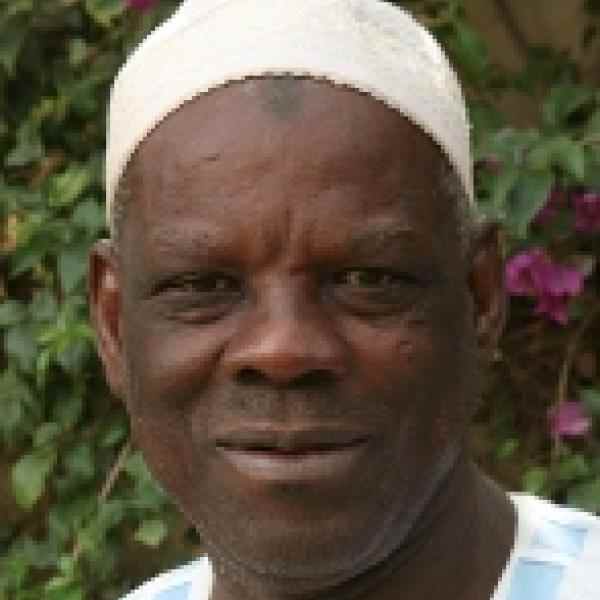

Introduction

Ladji Niangane has worked with farming communities along the banks of the Senegal River for more than thirty years. Farmers in the Sahel depend on their connection to this river, and it serves as a measure of greater problems like drought, pollution, and overexploitation. By stressing the importance of this waterway and building up a network of farmers, Ladji has been able to introduce innovations in sustainable irrigation, diversify crops, and improve local incomes and health indices. Today, his integrated network of knowledgeable farmers doesn’t just protect the Senegal River; it works together to respond to increasing threats like climate change.

The New Idea

Ladji's approach has been to involve local farmers and those from the surrounding regions in his efforts to pilot new approaches to economic livelihood. He began in the late 1970's by introducing the first cooperative to Mali and negotiating the price of products in the local markets. At the time the farming system was based on government fixed prices for all agricultural produce. In 1978 he pioneered the effort in Mali to allow cultivators to diversify from cultivation to into raising animals like cows and goats. At the time the farming system was organized around the strict separation of these farming practices. Ladji's innovations in irrigation made it possible for farmers along the banks of the Senegal River to plant banana and papaya on a large scale, an idea which had been deemed impractical to that point because of the drought conditions in the region. Ladji also pioneered the planting and sale of a much wider range of vegetables than had hitherto been the case. This innovation has changed the diet of local farming communities which has had a documented effect on the health of the local farming population in the area. Previously the local diet relied heavily on cereals, meat and milk, with few if any vegetables. Ladji also introduced the systematic cultivation of seed varieties in this region of the Sahel. His first successful effort involved Galmi violet onions that had previously been grown exclusively in Niger. Producing this seed required long-term, focused attention to irrigation and waiting for the second generation crop to flower and set seed, in addition to careful harvesting and storing. His current efforts to stabilize the banks of the Senegal River are focused on a mix of netting, tree planting and crop cultivation to prevent erosion. He is also a leader of a pan-African organization that monitors and resists efforts by multinationals to obtain trademarks on available local seed varieties.

The Problem

In the 1970’s the Sahelian region was gripped by a multi-year drought that severely affected local farmers. Ladji had been working as a laborer representative in Paris, but he decided to return to Mali and figure out solutions to this problem. He had been raised on a small farm and so he supplemented that knowledge with training at research centers and farms in France. He and thirteen others who shared his same vision were given sixty hectares of land in Mali by a local military governor to establish a farm and come up with innovative solutions to the problems faced by farmers.

In addition to introducing new approaches to irrigation, crop planting and farm management, Ladji soon realized that part of the problem was the government controls in the farming sector. From 1976 to 1991, when the government changed and the farming sector was allowed more flexibility, a great deal of his time was spent convincing government officials to let him do things like set up a cooperative and negotiate prices at the local level instead of selling unprocessed produce to the government for a pre-set fixed price.

With the shift away from military government the challenge shifted to disseminating knowledge across the region and making these innovations sustainable. Ladji created a network of farmer-supported community radio stations to spread news of the innovations and recruit farmers to spend time learning new techniques at his farm in Sinakota. He also organized networks of farmers along the banks of the Senegal River to share knowledge and further disseminate new farming practices in an area that encompasses four countries and whose land mass is the same size as the country of Senegal.

The issue that occupies Ladji now is food sovereignty. The threats come from several directions. The first is shifting climate conditions, which have produced much higher than normal periods of flow on the Senegal River, causing riverbank erosion and threatening river bordering farms. The second challenge comes from multinational corporations which seek to patent and trademark local seed varieties as something they have developed or created, thus causing farmers to have to pay more for such seeds than if they were commonly available.

The Strategy

Ladji is turning to the extensive network of farmer’s groups that he has organized to tackle the challenges posed by climate control and multinational taking of the rural farmer’s patrimony. The most common prescription for riverbank erosion is to anchor the areas closest to the river with netting held down with large stones, and then to plant a perimeter of deep rooted trees several rows deep along the riverbanks. Cultivation in the areas near the riverbank is commonly shifted from products like ( ) to products like ( ), which can more readily survive in conditions where the riverbanks are sometimes overtopped.

Ladji is a founding member of ( ) a Pan African organization that alerts farmers to efforts made by mulitinationals to patent local seed varieties, and to file protests against such actions. So far the organization has halted the consideration of (?) such patent applications and is in the process of actively contesting (?) more such applications. The organization is actively looking for ways other than protests to contest such takings of local agricultural patrimony.

The longer term plan is to build this capability across farming communities bordering riverbanks that are faced with the same kind of climate and man-made challenges. Ladji’s advice is regularly sought by farmer’s organizations in other parts of Francophone West Africa, notably in Guinea, Senegal and Burkina Faso.

The Person

As a young person Ladji was an activist involved in political causes that led to him being refused continuing admission at university. He left Mali and worked in the Congo and Guinea before moving to France. In France he was the first African to be an elected labor representative in the Confederation General du Travail. He represented the rights of French workers in negotiations with their employers and formed the Association Culturel des Travailleurs Africains en France. The main purpose of the Association was to teach literacy to African-born members of the CGT.

Inspired by the stories of drought in the Sahel Ladji formed a group of fourteen Africans who decided to return to Africa and come up with farming solutions to the conditions of drought. Their subsequent return to take up farming inspired ten other groups to do the same. Four members of Ladji’s original group of fourteen continue to work with him on the land that was given to them by the local military governor in Mali in 1976.