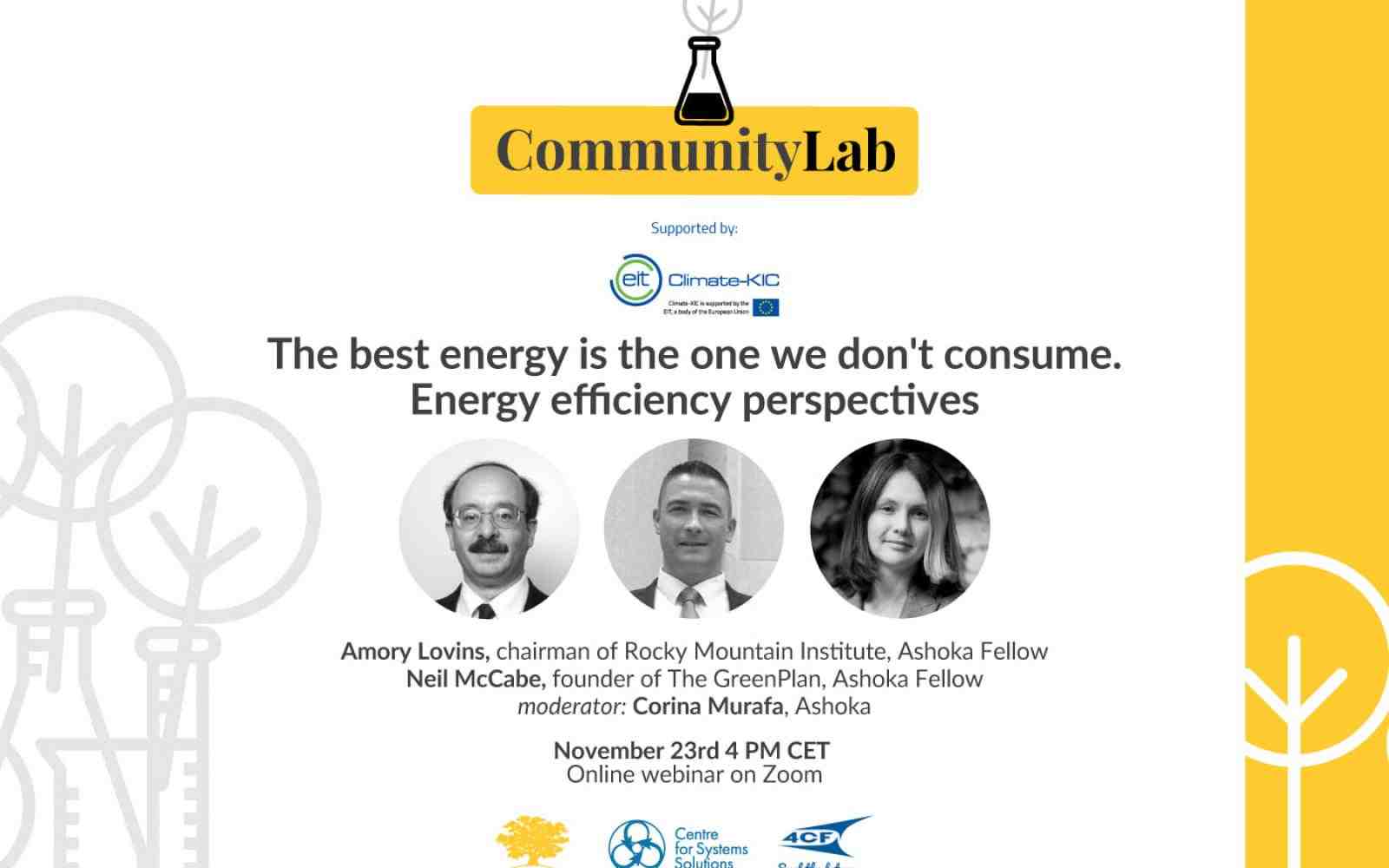

At a webinar organized by Ashoka and Climate-KIC’s Community Lab under the title “The best energy is the one we don’t consume”, two champions of energy efficiency spoke of their experience in saving huge amounts of money while boosting people’s morale through drastically limiting the waste of energy, both at the workplace and at home.

Their testimonies were followed eagerly by the participants, Central and Eastern European changemakers and social innovators taking part in this Community Lab kickstarted in October to form and fund transnational collaborations that turn existing islands of green action into a vibrant archipelago powerful enough to transform the region.

The first speaker to take the floor at the event, which took place on 23 November and was moderated by Ashoka’s Corina Murafa, was Amory Lovins. This American physicist of Ukrainian descent who told the audience about how he built the ultra-energy efficient 4,000 square-feet (or over 370 square meters) where he lives and works in Old Snowmass, Colorado.

Situated in the Rocky Mountain, where temperatures reach at times 40 negative degrees Celsius, Lovins’ residence does not have or need heating thanks to a carefully thought design with which he literally sealed the house. “This building has no heating system and it was cheaper to build it that way,” he said, speaking from the very same space he’s been upgrading for decades, turning it into a global example of energy efficient architecture and engineering.

The secret, Lovins explained, was “super-insulating it” -using, among other elements, “super-windows” consisting of several layers equipped with technology that allow light but not heat to pass. Besides, a ventilation heat recovery system has been installed in the building. “As a result, [it] is 99 percent passive solar heated, 1 percent active solar heated,” explain its owner and architect, who said that this model has been successfully replicated in both new and old buildings and is applicable in any climate.

From another window of the Zoom-supported webinar spoke Neil McCabe, a full time Irish firefighter turned energy efficiency guru. His recipe to dramatically reduce waste and consumption in public buildings and facilities have already saved no less than 11 millions of euros to the Irish taxpayer and is looked at at the EU level as a model of success in this field.

How did a firefighter become the visionary brain behind it? “I kind of stumbled on the energy scene completely by accident,” McCabe said. It all started when he decided to lead his colleagues into collecting used batteries as a way to improve the morale of the team through positive behavioural change. The success of this modest initiative made him think of the many ways they could make the fire station more sustainable by simply changing their habits, so he launched a campaign to save 10,000 euros from the utility bills.

They achieved their goal through measures such as segregating waste to avoid landfill taxes or installing thermo-dynamic solar collectors. The success drew the attention of the fire brigade management and the Dublin City Council, and the plan was replicated in several fire stations and public buildings across the capital. McCabe has since systemized his vision in what he has called The Green Plan, whose seven themes are Energy, Water, Waste Biodiversity, Transport, Society and Procurement. This integrated agenda has become a blueprint for the administration’s efforts to make their infrastructures sustainable. The practices it promotes include using wastewater in fire extinction, setting up social ventures to manufacture retrofitting equipment and opting for local procurement in order to reduce fuel consumption.

The model has been enthusiastically embraced by the authorities. “They said, ‘we like saving money, how can we save some more?’,” McCabe recalled at the webinar. Social activists usually complain about how irresponsive are politicians when presented greening solutions or new practices. McCabe’s experience is radically different. “They ask me to come with the next steps to save more energy”.

“The more you can influence anybody -any business, any country, any economy- to save money, the fastest you can get them to change their behaviour,” he said on the approach that got politicians asking him “what they have to do next”.

Combining sustainability with financial profit has also proven a highly effective way to approach potential partners for Amory Lovins. Besides offering a stunning example with his Old Snowmass house, Lovins works to influence policy and attract private companies to the green cause through his Rocky Mountain Institute.

He has worked with utility regulators, whom he encourages to reward electric and gas companies for cutting the energy bill, but also with large companies. “We help them discover, rather than persuade or harang them, that they will make more money, deliver better service, have less risk, less cost, have more fun, attract and retain and motivate better people if they focus on energy efficiency.”

Lovins -who was referred to by the moderator, Corina Musafa, as “one of the global godfathers in energy efficiency”- advocates constructive engagement to broaden the base of the green sustainability movement. Rather than expect people, companies, politicians or business representatives to adopt one’s worldview, it is more fruitful to “speak to … [people’s] concerns in their language”, find common interest and a convergence in outcomes that are favorable for both parties.

“You cannot depress people into action, you have to interest and inspire people into action,” he said, and outlined the importance of “being able to work with people who don’t believe or care about climate.” To gain the cooperation of a group of climate skeptic US conservative businessmen in one of his projects, for example, he highlighted the positive economic impact energy efficiency would have for their companies, as well as for national security - a common good often put at risk by the dependency on foreign oil or other forms of energy.

Lovins derived this view from aikido politics, named after the modern Japanese martial art whose aim is redirecting the strength and momentum of the attacker in order to protect oneself without harming the opponent. “In aikido politics you don’t fight with an opponent, you dance with a partner,” Lovins said.

“You honour their beliefs as if they were your own even if you disagree with them. And you are committed to process not outcome in the belief that fellow good process will emerge a better outcome than anyone had in mind in the first place,” he added.

He confessed to having needed “some decades to graduate from confrontational, oppositional thinking and tactics” and eventually adopt aikido politics, which he called “a very effective, insidious technique” that brings great fun, often works and has a lot to offer to the climate movement.