Introduction

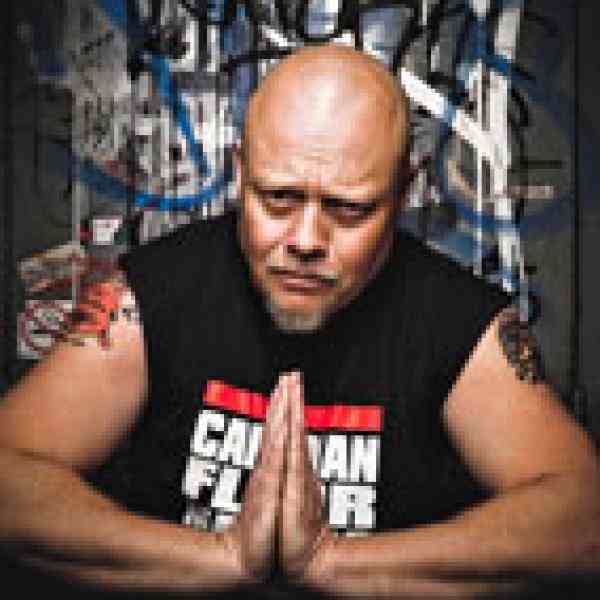

Steve Leafloor is creating young leaders among First Nations and Inuit communities where sexual abuse, family violence, and school desertion are common. Using a blend of hip-hop dance and music and traditional Inuit performance arts as a hook, he guides youth and other community members to create comprehensive networks of support and solutions to these mental health crises.

The New Idea

Reaching some of the most isolated communities in Canada, Steve is fostering a new sense of cultural pride among First Nations and Inuit youth and other related groups by helping them overcome traumas including sexual abuse and other forms of emotional and physical violence. His model, BluePrint for Life, draws on the positive aspects of hip-hop, an Aboriginal culture that supports youth, and traditional Inuit arts such as throat singing, drumming, and traditional Inuit games. It also brings together role models from other marginalized cultures. In doing so, Steve motivates and empowers young people to hear each other’s experiences of violence and helps them to create safety plans and new ideas for healing and managing anger. They feel comfortable voicing their personal struggles in Steve’s peer-to-peer support environment, disrupting old habits that neglect or ignore the issues of violence and abuse. This environment in turn gives rise to a strong support network, where youth can rely on and trust each other, thereby helping to build their self-confidence and resiliency.

Beyond just peers, Steve brings other stakeholders into the support network to build an integrated safety net and also involve key leaders in the dialogue. By participating, they grow more conscious of some of the underlying social problems affecting their communities and are more determined to stop them. For 90 percent of the youth, Steve’s program is the first chance they have had to engage with other youth, social workers, and community members to discuss their experiences of sexual abuse and how to create safety plans for themselves. Steve also supports the youth to launch their own healing-dance groups in their communities to ensure continuity, with support from adult mentors. These alliances with teachers, elders, and youth also trigger a process to create intergenerational connections that could last a lifetime.

The young people in Steve’s programs also become critical assets to expand his work; as they become leaders in their community, who launch their own dance clubs and engage their younger peers. This mainstreams the use of dance to address mental health issues. To maintain the viability of his model after he leaves the community, Steve created a series of 30 one-minute motivational videos in which diverse youth role models give other young people practical ideas to help them address abuse and mental health issues in moments of crises. His goal is to develop a smartphone application, so youth can download the videos onto their mobile phones and smartphones at their local schools. Steve has created a variety of ongoing resources that are easily accessible, which help encourage entire communities to talk about and address youth mental health issues.

The Problem

There is a loss of identity, community pride, and hope among many First Nations and Inuit youth. This is manifested through addiction, unhealthy lifestyles, violence, abuse, and suicide. For example, the suicide rate in Nunavik—the autonomous northern third of the province of Quebec that is predominately populated by Inuit Peoples—is more than 7 times higher than in the rest of the province. For youth ages 15 to 19, the suicide rate is 46 times higher, and for young adults between 20 and 24, the suicide rate is 23 times higher.

Most of the young people Steve works with are dealing with a loss of hope. (In one community, Inuit parents estimated that 95 percent of the youth Steve works with had been sexually abused.) There is often a history of family violence, addiction, extreme shyness, depression, teen parenthood, anger management problems, bullying, and poor school attendance. In addition, many remote Northern communities suffer a loss of culture and are disconnected from the rest of Canada. But despite these complex issues, there are also great strengths to build upon, such as the importance of family, and traditional culture.

These communities face very complex issues stemming from the effects of colonization and the long-term effects of residential schools, lack of housing, and poverty. The legacy of residential schools has had a lasting effect on the mental health of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. There were about 130 schools across the country, from the first in the 19th century to the last that closed in 1996. In all, approximately 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools. Further, there is an overwhelming lack of funding and resources for education, social work, cultural activities, and access to mental health resources in remote Northern Canadian communities. The federal government funds Band-operated schools at a level lower than what provincial and territorial governments provide for elementary and secondary schools. For First Nations Band-operated schools, the majority of available funding is used to pay for the costs of educators and staff—there is no designated funding to pay for programs and services such as libraries, technology, sports, music, activities to support improved student achievement, indigenous language support, or cultural programing.

The Strategy

Steve’s program focuses on anger management, peer-support, healing, and creating an inventory of positive support in the lives of youth. Steve creates various intensive week-long programs that are integrated into existing programing during the school year. The opportunity to learn hip-hop dance and positive hip-hop music blended with traditional Inuit arts, hooks the youth to participate in his program. They engage in making music and choreographing dances with other community members, thereby learning teamwork, creative expression and collaboration with peers who have different abilities.

By inviting community members to join the dance troupes, Steve helps create a notion of empathy among the youth and individuals in their lives with whom they might have had difficult relations. Community leaders like police officers, social workers, teachers, and even the mayor, are critical participants in his workshops. Steve relies on the individual community context as he designs the most influential means of involving the community. For example, youth who used to have unstable relations with police work with them to choreograph a dance and then discuss the experience of the exercise. These experiences transform the way youth perceive law enforcers and vicé versa. In addition, these improved dynamics are demonstrations of compassion that affect the well-being of entire communities.

Steve ensures that the workshops are fun, physically intense, and ultimately healing. He trains youth facilitators, outreach workers, and top dancers to lead the workshops, in tandem with the community leaders for certain parts of the programing. Much of Steve’s methodology is based on experiential learning, which is a stated value of traditional indigenous cultures. Although positive hip-hop lyrics, dance, and graffiti art entice them to participate, the priority of Steve’s work is healing and mental health. Steve integrates various culturally-sensitive techniques in his week-long programs, including therapeutic approaches such as cognitive, group, laughter, play, and art therapies. He also uses mentorship, role modeling, meditation, and trains the youth in resiliency, anger management, and safety planning. He supports each young person to create a personal inventory of family strengths and community resources, disclosure and healing path stories, self-regulating techniques and supports them to set goals. Another part of Steve’s programing is Daring to Dream, in which he teaches youth about positive risk-taking, self-discipline, leadership training, and cooperation skills. Steve tackles issues progressively throughout the week, beginning with topics such as anger management, bullying and eventually moving toward tougher issues such as addiction and sexual abuse.

Steve uses role-playing to support the youth to practice empathy and cooperation when intervening in situations of abuse, self-harm, violence, disrespect, or sexual health. They help him create the scenarios to ensure relevance to their communities. The role-playing scenarios also include problem-solving on how to create extracurricular groups in the community. Steve helps them create ground rules for themselves and basic “how-to” support by playing out various situations that they face every day. Further, Steve has created a code of ethics for his dancers, which builds a relationship of trust with the First Nations communities; allowing him to return (usually once or twice a year) and continue assisting youth with mental health issues through dance.

Once Steve’s group leaves, he ensures the youth are equipped with support from social workers, local community centers, and teachers to help them launch their own hip-hop/after-school groups. Involvement in these groups contributes to their positive mental health, helps them grow physically (through exercise and healthy eating) and emotionally, and serves as a long-term peer and adult mentor support system. The dance clubs are often housed out of the local wellness or community centers that offer space, snacks, connections to nearby communities, and adult support to keep them sustainable.

One of Steve’s interventions is a series of more than 30 one-minute motivational videos in which diverse young role models relay messages such as speaking out against abuse and confiding in someone when feeling depressed or suicidal. The videos are meant to motivate youth in the exact moment that they might be thinking about self-harm or fleeing an abusive situation, and will be readily available as a resource on their mobile phones and computers. They can download the videos at their local schools onto their mobile phones, an example of creative use of accessible ICT technology. By employing multimedia tools, Steve is building a system that is replicable across all Indigenous communities.

Since 2005 Steve has reached more than 4,000 youth in Inuit and First Nations communities in the Arctic and in Canada’s inner cities. Nunavut’s government officials commented after the flagship workshops in Iqaluit that Steve’s model was, “the most substantial youth engagement programming in 20 years.” In December 2011, Steve piloted his model to some of Alberta’s maximum-security youth prisons, where 86 percent of participants deemed that after participating in the program, they had more strategies they could use to deal with their anger. Over the next three to five years, Steve envisions spreading his model to more underserved communities in Canada’s North, and also working with newly immigrated families in Canada’s urban Centers.

As he expands, he also seeks to diversify his financial partners. Steve’s program has recently signed a multiyear deal partnering with the Kativik Municipal housing board to reduce vandalism in social housing, and is partnering with the national Inuit women’s association (Pauktuutit) on some truth and reconciliation projects, to bridge generations who suffered trauma from the residential school system. Currently all of BluePrint for Life’s funding is generated through a fee-for-service model, where clients pay for the programing they provide in communities. Clients include school boards, wellness centers, band councils, and most recently Corrections Canada. Steve is looking into creating a non-profit arm so that BluePrint for Life can accept donations.

The Person

The son of a pastor, Steve grew up in the Prairies in a family that was very active in community development. His family home was a full house with nine people, which included a disabled aunt and an adopted sister, who is African-Canadian. Growing up and supporting his sister, he had a first hand understanding of racism and exclusion.

At 15, Steve’s family moved to a small town in southern Ontario near Windsor, where he was a victim of bullying in high school. To withdraw and avoid this treatment, he started to experiment with drugs and was involved with break and enters. Yet quickly he realized that even without being bullied, such risky behaviors were still harmful to him and his well-being, so he decided to channel his anger and energy into physical activity. Steve was always interested in roller-skating and its connection to 1970s Motown and funk music—and would attend the disco, funk shows, and roller-skating performances.

Steve decided to practice roller-skating seriously and became one of the top skaters in the Windsor/Detroit area in the mid 1970s. Dancing on skates became a way to heal from his anger and gain confidence. As the disco/funk movement highly influenced the early days of hip-hop dance and music, with lyrics tied to oppressed communities speaking out and a break-dance style of dancing similar to roller-skating, Steve became very interested in hip-hop culture. He always kept a core group of friends who focused on the positive aspects: positive lyrics, self-determination, and healthy competition. Scott formed his own dance group that performed for famous musicians such as James Brown, Parliament, Grandmaster Flash, and recently, the Black Eyed Peas.

Steve completed his bachelor and master’s degrees in social work and traveled around the world between his degrees. While completing his masters in the mid 1980s, Steve convinced his professors to let him complete his field research in a low-income community. This was the first time he used hip-hop as a tool for getting young, at-risk people to talk about the issues they faced, such as violence, drugs, and poverty. This program boosted the confidence of the young people and encouraged them to launch the epic Freestyle 85 hip-hop festival in the center of Covent Garden, in London, under the tutelage of Steve as the lead entrepreneur. The festival ended up being one of the most influential experiences in hip-hop culture and sparked a global ripple effect in communicating empowering and positive messages via all the elements of hip-hop.

After returning to Canada to earn his master’s degree, he worked as a senior social worker at Children’s Aid for nearly a decade. In the early 1990s Steve decided to start his own business selling holograms. He was the first to sell a rare Dizzy Gillespie hologram, which spurred Nortel to contract him to create a hologram of a famous satellite photo. After six years, Steve’s business was affected by the recession of the 1990s and he returned to Children’s Aid.

While Steve practiced social work for a few years, he continued breakdancing on the side and performing for many famous musicians.

In 2005 Steve wanted to support his sister, who married a local Inuit man in Iqaluit and they had three children together. In ongoing discussions with his sister, he realized there was a lack of resources in the North to address the ongoing effects of residential schools that are typically felt by everyone in the communities and often manifested in anger, abuse, and addiction.

That same year, Steve left Children’s Aid and created BluePrint for Life, merging his early experiences in hip-hop and social work to address the emotional and physical trauma endemic in these Aboriginal communities. They have been awarded an outreach award by former Governor General Michaelle Jean and the first group from North America to be recognized as a top five finalist by the prestigious Freedom to Create Awards.