Introduction

Laszlo Jakubinyi proves that individuals with intellectual disabilities, of all levels, can thrive as dedicated employees and live productive lives. Laszlo has created a replicable rural approach for people living with moderate to severe levels of intellectual disabilities. Laszlo’s approach is spreading to Poland, Romania, and Moldavia.

The New Idea

Laszlo has developed a new health care delivery system for moderately and severely disabled people. His approach facilitates the idea that people with significant autism and other mental disabilities can manage and excel in employment. To prepare intellectually disabled people for the workforce, Laszlo relies on a number of insights. Laszlo believes a multi-stage rehabilitation model is the best way to prepare intellectually disabled people for independent lives. He begins with a physical space, where people with various intellectual disabilities are integrated, including non-disabled people. When participants are ready, they enter a “sheltered” employment program where they undergo paid work for four hours a day (i.e. contracted by Laszlo’s organization), and experience on-the-job training according to their skills and capacities. Once comfortable in this environment they move on to a longer-term “transit” employment program with more stringent responsibilities (i.e. arriving to work on time and finding their own means of transportation to and from work), and undergo evaluations to prepare them for the open labor market. This staged process mimics the fundamental idea that humans first need basic shelter and food, then access to things like employment and a steady income, in order to achieve dignity and fulfillment in life.

Laszlo’s second insight is that any approach to rehabilitation should mirror life’s setbacks and successes. He therefore constructs his model so participants can retreat if needed, regain confidence, and then re-engage with the program. Emotional crises do occur, such as a death in a family or a break-up, which can jeopardize an individual’s rehabilitation progression and set them back to the sheltered stage. Therefore, participants have access to a crisis center which offers therapy, including theater and puppetry therapies, to support them during emotional set-backs.

Laszlo also insists that rehabilitation services which integrate a broad range of disabilities are much more effective than a closed community limited to one or several disabilities. His open model differs from traditional services by providing services and activities that cut across numerous disabilities, physical to intellectual, and moderate to severe—and even incorporates non-disabled persons. For example, a blind person may work with a severely autistic person to train guide-dogs.

The Problem

In Hungary, 2.5 percent of the Hungarian population lives with autism and mental disabilities. Of this total population, about one half is enrolled in primary or secondary education, whereas only seven percent is employed. Furthermore, 85 percent live at home, with parents who have dedicated their lives to their upbringing and rehabilitation, while 14 percent live in state-run institutions with over 300 people, where their isolation runs deep and keeps them invisible from the majority of society. The final one percent lives in independent apartment homes of approximately a dozen people, primarily run by disability organizations. These numbers begin to uncover the major opportunity to better integrate intellectually disabled people into society, particularly into the employment sector and independent housing.

In Hungary during the 2000’s, the handicap field, particularly the autism field, was increasingly gaining attention. Questions were being asked such as, what services exist after school for children and for adults when they are at the age to leave home? And what happens when parents are no longer able to care for their disabled child? Parents and guardians wanted smaller, more intimate institutions to take care of their handicapped sons and daughters so they set up associations that worked to build more independent apartments. However, although these housing facilities offered leisure time and rehabilitation services, they were not sustainable solutions for disabled individuals. Without opportunities for work and independence, their disabled inhabitants were continuously bored and unfulfilled.

Another problem during this time was that existing rehabilitation programs in Europe often ignored the need to provide disabled people with the ability to cope with crisis situations. The occurrence of crisis situations decreases the possibility for people with intellectual disabilities to gain stable employment and live independently. This challenge is further strengthened by the prevailing notion that people with disabilities are rather problematic employees and do not bring value to a company. In Hungary, 75 percent of adults with moderate disabilities and 97 percent of adults with profound intellectual disabilities are qualified as “unemployable” in the mainstream labor market.

The existing healthcare delivery system for disabled populations, which relies on institutions or personal caretakers, is unsustainable during an age where much consideration is given to human rights and human dignity, as well as to innovation solutions to pressing social problems. In the case of disabled populations, an entirely new European-wide approach is needed, along with a fundamental change in attitude towards the ability of moderately and severely disabled people to live independent and dignified lives.

The Strategy

Over the years, as Laszlo worked closely with the intellectually disabled, he began to see that people with autism and severe mental disorders have the potential for almost entirely independent lives, including decent employment and an autonomous living situation. Laszlo is ending the notion of institutionalizing intellectually disabled people by demonstrating the success of open and independent living facilities where severely intellectually disabled people find paid work and those moderately disabled become prepared to enter the labor market.

The core of Laszlo’s approach is a farm, which acts as an open community; its disabled inhabitants engage in farming activities, animal husbandry, vegetable production, and crafts work. The farms provide a physical space for people with various intellectual disabilities to interact, but also includes non-disabled people, such as youth staying at the farm’s hostel, buyers of the farm products, and participants of the open events organized by Szimbiózis. Szimbiózis farms have become the model for providing rehabilitation services to disabled people in Hungary’s northeastern rural communities, and Laszlo is working to make his multi-stage approach the standard delivery service for disabled populations. With four farms established, Laszlo will spread to all 19 counties across Hungary and take his approach beyond Hungary, to nearby countries with similar service delivery problems.

A successful element to Laszlo’s approach is the creative methods he uses to keep disabled persons engaged and working together across their spectrum of disabilities. In 2007 Laszlo began to interact and eventually employ people with physical disabilities, instead of only intellectual, on the Szimbiózis farm and its activities. He observed that the creative combination of disabled peoples’ skills results in better work performance. Laszlo therefore has people with physical disabilities supervising and working with those with intellectual disabilities. For example, a woman with only one arm will work with a strong boy with a severe intellectual disability in the production of goat cheese. She oversees the process of cheese production and helps to instruct the boy, while he lifts heavy pots or other activities; or, a man with schizophrenia supervises the processing of vegetables in the kitchen with several other employees with autism able to efficiently peel the vegetables. In 2010 Szimbiózis’ activities in Miskolc, a town in northeastern Hungary and the location of Szimbiózis’ first site, employed over 160, people of whom 100 are disabled and 60 are employees.

Using pictogram flow charts that easily define and describe various work processes has also strengthened the results of the employee training program. Severely disabled persons receive simple pictured step-by-step instructions for their work, such as how to make handicrafts. These instructions leverage their skills, i.e. attention to detail, precision, and unerring focus that is common for people with autism, as well as other intellectual disabilities. The pictograms have also been used to define the work processes for employers. Laszlo advocates having pictograms as an accepted standard assistance tool for employees with severe disabilities. He is building a universal foundation for these tools by developing a European-wide database where pictograms are uploaded and employers can search for them depending on the work process they are implementing. The database will also spark new ideas among employees and rehabilitation organizations about the ways disabled people can be successfully employed.

Laszlo’s work with guide dogs is a further example of the unique methodologies he employs to engage individuals across varying levels of disability. When he was approached by blind people to help them with employment opportunities, he decided to transform a building on the farm into a guide-dog training center. Besides benefitting the blind, this program created an additional job placement and therapeutic activity for people with severe autism to care for the dogs. This joint dog therapy approach has been so successful it has spread across Hungary and the municipality where Szimbiózis is located will fund an additional guide-dog center in town.

The majority of Szimbiózis’ funding currently comes from the Hungarian government and the European Union. Laszlo is looking for ways to lessen the organization’s reliance on government funding. He has viewed this as an opportunity to set up several related companies that have assumed some of the farm’s activities, including a catering and a transportation company (i.e. to take disabled to and from the farm, and children with special needs to their schools). Szimbiózis coordinates with its disabled staff and the catering company to deliver lunches to various locations and organize the home delivery of milk. A hostel on the farm also welcomes school children who come to experience farm life as well as learn more about disabled life. All the activities that fall under his model of social enterprise apply the idea of mixed working groups that complement each other with their specific skill-sets. Szimbiózis’ business activities therefore generate a sustainable funding source (i.e. 10 percent of Szimbiózis 2010 budget, and growing) which is reinvested back into organizational activities.

In 2003 Laszlo founded an agency that provides intermediary assistance to facilitate the matching process between companies interested in employing intellectually disabled and disabled people themselves. The agency helps to define their skills and provides proper on-the-job training. While the agency initially focused on people with mild disabilities and autism, after learning about the need of employers, he soon realized that people with severe disabilities could also be hired in settings outside of the farm. State employment offices soon began to send disabled individuals to Laszlo’s intermediary employment agency. To date, two other organizations working with the physically disabled have replicated his employment matching model.

Laszlo has also begun to influence policy and gain attention in Hungary across a range of venues. He launched the Disability Work Group in the northern eastern region of Hungary to advocate for regulations enabling the employment of people with intellectual disabilities. Furthermore, Laszlo helped to finalize a court case this year which set a precedent for orphans with severe intellectual disabilities to be employed. He has also begun a media campaign to portray what it means to be employed for persons with disabilities. He produced a movie showing the meaningfulness of the first salary for disabled persons. With the slogan “I would like to pay taxes” in Hungary, the film has been received with great interest and significant attention. Laszlo is also partnering with local authorities to convince municipalities to transform public housing into flats for up two to three people with disabilities, who share its expenses. In 2007 the Szimbiózis Foundation inaugurated the first blocks of apartments for 12 people with severe intellectual disabilities and in January 2009 another block of flats opened.

Laszlo is now working on a strategy to find and help local community members to develop their own value chain of activities to serve disabled populations. For example, Laszlo and his team are working with parent groups from different towns and villages to help them to write a project proposal, obtain permission from the municipality, and attain government funding to replicate elements of the Szimbiózis model to their own contexts. He is also interested in creating a quality of life assurance system that measures the true quality of life of a disabled person, in addition to a knowledge base to facilitate the program’s spread and to maintain its quality. The Disability Work Group is assisting to further replicate elements of the model, share methodologies, and develop standards for success (e.g. the home centers must be open and include various levels of disabilities both mental and physical). Laszlo’s work with quality control, spreading networks, and creating industry standards is moving society closer to a world where institutions are phased out and a value chain that supports the independent living and employment of disabled persons has become the norm.

To date, Szimbiózis, has either established or assisted with the development of four farms across Hungary, with two others being developed in Romania. Laszlo is also advocating with state authorities to include people with intellectual disabilities in the mainstream labor market, and elements of his model are being picked up by other disability organizations. Ultimately, Laszlo envisions a world where disabled people are living independently, instead of excluded and isolated from mainstream society in institutions and homes.

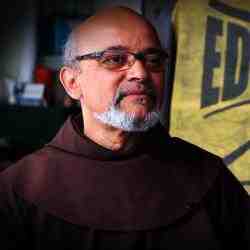

The Person

Laszlo was born in 1969 in the northern part of Romania in a commercial logging and mining town. His family background is a mixture of nationalities and cultures, i.e. it was normal to celebrate various religious holidays throughout the year. Although Laszlo’s mother language is Hungarian, he was a minority in his town, speaking Hungarian at home and Romanian in school.

In the 1980s, when Laszlo was 14-years-old, he became involved in the underground Hungarian theater. The Securitate (Romanian communist security forces) picked him up, jailed him, and beat him for his involvement. However, Laszlo continued to reject social norms with which he disagreed. He soon became involved with a community group that collected food to bring to a local psychiatric hospital. The hospital’s patients lived in atrocious conditions: Half-clothed men and women were kept in an attic of concrete, where there was only a hole for a toilet and metal beds to sleep in. After Laszlo brought food to them for the first time he was not able to eat that day; he was so disturbed by what he saw. Even the animals at his house did not live in such poor conditions. Laszlo began to return to the hospital once a week, then twice a week. He visited, bringing food and clothing for over three years. He believed that the patients waited for him and he had a duty to return. From this point, Laszlo devoted the rest of his life to bettering the lives of the intellectual disabled.

When Laszlo entered the Romanian army at 18 he immediately sought out a psychiatric hospital where he could volunteer. After the army he decided to organize summer camps for disabled people, and with 8 other young people he received free space from a church to develop a center. However, funding was always a challenge for his work and it was hard to get the center up and running. Laszlo decided to study special education in Budapest, but lacking adequate financing and struggling to be accepted by the school for his revolutionary ideas on how to best serve disabled populations, it took him 13 years to complete his studies.

In 1992 funding from the Knights of St. Columba enabled Laszlo to build the church space into a rehabilitation center for intellectually disabled individuals, but in 1997 he ran out of funding and was unable to convince the Romanian government to support him, refusing to recognize his Hungarian degree. Feeling tired, he accepted a job as a teacher in Hungary and also worked for a citizen organization to set up a home center for disabled adults. Laszlo experienced setting up home centers with a local church and the Budapest municipality. All along, he knew a home center is not a solution for the integration of disabled adults into society. The centers remained against the employment approach for which Laszlo strongly advocated. Laszlo therefore founded the Szimbiózis Foundation in 1999. For the first three years he worked as a volunteer and in 2003 he made the decision to become a full-time staff person and has been committed in this capacity ever since. Laszlo’s approach is now to focus more energy and efforts on scaling to a national and regional level.