Introduction

Evidence shows that inmates who are able to work while in prison are less likely to re-offend. Many programs around the world give prisoners new skills for a life away from criminality upon their release. This has been very difficult in Italy because a law - initially designed to protect the exploitation of prisoners -forbids work in prison unless it is paid with competitive salaries. By creating a powerful brand, Luciana delle Donne has found a way to hire hundreds of women in prisons and to embed them in a production system which begins and ends outside of the prison. Women are indeed hired with a regular contract, which pays for their legal expenses and allows them to save up for their first periods after detention. She compensates for the lower productivity inherent to work inside prison by working with for-profit companies that donate materials to Made in Carcere. Her model has been taken up by the Minister of Justice as the only functional example of paid work in prison.

The New Idea

Luciana’s mission is to ensure detainees can work and be paid while in prison, allowing them to use their imprisonment as a chance to learn new skills and secure employment once outside. Luciana is working to give a second chance and a new life to both people and products. Made in Carcere (made in prison) offers women real waged jobs while serving their sentences. They learn new skills that will allow them to choose employment rather than reoffending once they are out. Made in Carcere’s women produce textile products both for consumers and on behalf of other businesses. At the same time, Luciana’s work has an environmental impact, as she gives a second chance to waste material. Luciana involves several businesses in the large Italian textile industry to donate unused fabric to Made in Carcere, reducing waste and cutting the cost of production, so that more of the income can be used to hire new workers in prison.

Her model is based on the idea that the waste of one industry can be reused while at the same time providing a job opportunity to those who need it the most. She began her work in prison with textile products, but her model has already tipped to other industries. As a local foodstuff business found itself with oversupply of flour, Luciana accepted their donation and found a prison with sufficient equipment for cooking large quantities of food. She began a new production of biscuits made in prison.

Inmates in Italy cannot work unless they are offered a wage. The available work opportunities are almost entirely relegated to internal maintenance and upkeep of the prison, without any training or concern for what would happen once the inmates are released. Luciana transforms detention into a time for learning. She sets standards that are comparable to those found in the outside world, giving women with little or no experience in the non-criminal economy, not only new skills, but also the experience of life in a real company. By keeping themselves busy, women tend to behave much better, to improve in other aspects of their psychological and social lives. They have new-found pride, as they can pay for legal expenses and send checks to their children and families. The current re-offense rate for women who have gone through Luciana’s program is 0%. As she tries to prepare women for their return into society, Luciana wants the same for Made in Carcere. By embedding prisons at the center of the manufacturing process (in between textile production and sales), she hopes to make sustainable change to the role of prisons in society.

For this reason the Italian Ministry of Justice (MOJ) has noticed Luciana and has assigned her the task of creating a network of all experiences of work behind bars in Italy and to connect them into a production system called Progetto Sigillo. Once the MOJ money ran out, the consortium of prison’s workshops continued to survive only because of the demand created by the Made in Carcere brand. Luciana has managed to achieve what the government has tried and failed to achieve in years: to profoundly change the nature of detention using work to empower inmates to begin a new life, while at the same time paying them a real wage, as the law requires. She can barely keep up the demand from more prison directors wanting Made in Carcere to set up working labs inside their units.

Luciana began in the local prison of her town Lecce. She then moved onto Trani in the same region. She now works with 12 prisons all across Italy. Furthermore, she has managed to organize the different one-off programs of work inside prisons into an ecosystem of production. Whereas most programs would end once funding was over, Luciana has kept those alive by creating more demands for her products outside of prison, so that more inmates could be given a job. She has created a network of prisons in which inmates can work to create an interconnected ecosystem and one sales channel with its own brand. The system can be implemented in more countries. The key difference to other programs that seek to offer employment to inmates, is that Made in Carcere has made the fact that these products are made in prison the central element of its marketing strategy. Wherever there are prisoners and industries with left-over material, Luciana’s model will be replicable.

The Problem

In June 2014 Italy was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for inhumane conditions in which prisoners lived. Life in prison is not easy anywhere, but conditions in Italy are particularly dire. Italy is second only to Serbia and Greece, in the whole of Europe in terms of overcrowding, with 147 inmates for every 100 assigned spots (tiny cells meant for 3 inmates, usually host 4 or 5).

Crowded inmates are in most cases not even able to spend much time outside of their cells as chances to keep themselves busy are rare: by the Italian law labor needs to be paid equally in the national territory, with no exceptions. While this law was meant to protect prisoners from exploitation, it has instead paralyzed most attempts to give inmates activities to work on, as they can’t be volunteers but need to be hired. Few or no businesses would think of hiring people behind bars. A few prisons have agreements with businesses so that easy and repetitive tasks, usually assembling products created elsewhere, can be performed inside the prison, but no product has ever been entirely designed and created from inside a prison.

In addition to difficult living conditions, inmates in Italy spend most of the time in prison without much to do. Several make new connections that will results in a new web of criminality: as soon as they leave prison they are more likely to re-offend. The rate of re-offence in Italy is as high as 70%. The rate is massively reduced for those who work. In a country with high unemployment such as Italy, the great majority of those in prison have never worked in the legal economy. Several projects across Italy sought to train inmates for one profession or another, but once funds coming from the government or donors run out, none of the attempts prove unsustainable as there is no demand for these products. Although work is known to reduce recidivism and improve harmony in prison, the great majority of inmates wishing to work cannot do so. The re-offense rate continues to be high.

A second parallel problem is that of industrial waste. The textile sector accounts for 12.7% of all manufacturing production in Italy and every year a significant proportion of the fabric and other textile material produced ends up wasted. This has an environmental effect and often a cost, as businesses need to pay for this material to be dumped or recycled.

As Italy is being pushed by the European Court of Human Rights to radically change the way in which it manages its prisons, Luciana has an opportunity to change detention time into an educative period and not just a time of seclusion from society. Her model is economically sustainable and has proven to work, making her chances of reaching all prisons in the country achievable. In countries with similar labor laws, her model will be able to provide paid opportunities that would otherwise be difficult. In those places in which work can be underpaid, she has a chance to improve inmates’ rights and standards of living by granting them a fair salary.

The Strategy

Luciana believes that detention should be an opportunity for people who have failed society and have been failed by it to learn new skills. Her strategy is to train women to learn a new skills in a new profession and to expect the same standards she would demand from employees outside of prison. This has the direct consequence of providing inmates with a clear route away from criminality, as they become employable, thus stirring them away from re-offending once freed. Luciana’s work also has the effect of fostering a whole set of “soft skills” such as self-esteem, collaboration and creativity. The women are initially involved in Made in Carcere as seamstresses, but several move up to become team leaders, designers, marketing managers, etc.

All of them have regular labor contracts, pay into social security and are paid competitive salaries. This allows them to send some remittances to their families and to pay for all legal expenses, thus leaving their detention period without any debt. Luciana began by offering work to 12 women in 2008. In 2015 she employed 89. This has a huge effect on inmates’ behavior and consequently the length of their detention. By keeping themselves busy, detainees are motivated, their days are full and the time to pick up a fight or break a rule becomes limited. By the Italian law, if an inmate does not receive any “behavioural note” in a period of six months, their sentence can be reduced by 45 days. Women working with Luciana have proved to improve their behavior visibly and their sentences have been reduced. This accelerates the return to life outside prison and cuts the cost of detention for the state, as well as contributing to freeing overcrowded prisons.

However, it is extremely unlikely that the women hired in prison can work as productively as in the outside world, even if the law requires them to be paid competitively. Most of them have never worked before, several are illiterate or poorly educated, many suffer from psychological trauma. Not being able to access information on the internet, or directly make a phone call slows the production process and lowers productivity. To continue hiring more people and offering them a chance to change, Luciana had to lower cost elsewhere: the cost for the raw material needed to be reduced. For this reason, Luciana has actively involved the outside world in Made in Carcere, especially the wider fashion industry. She has begun to reach out to large and small businesses in the textile and fashion industry asking them to donate their left over material. Sometimes it is a box of silk, sometimes is a truck full of fabric. She currently purchases 30% of the material and gets 70% donated. She would like this proportion increase to 10/90 in the next years. This system also has an impact on the environment, as it focuses on material to be reused and given a second life.

Her model is completed by connecting the work inside the prison not only to other industries, but to responsible consumers. Made in Carcere is therefore made into a powerful brand and its products are sold through dedicated shops, online or through third-party retailers. The more Made in Carcere products are recognized and sold, the more inmates will be able to be given a contract. For this reason, Luciana began to branch out in her requests to businesses to donate their scrap material beyond just fabric in 2014. She has started to accept donations of other materials and to search for new prisons who would want to start a new Made in Carcere production lab. A ton of flour has led to the production of biscuits. When she received a cargo of pallets, she designed “vertical gardens”, wooden structures which occupy little space and on which inmates can grow plants and vegetables, to be used in the prison’s kitchen. At the same time caring for plants has a therapeutic effect on inmates. She is changing how detention should be lived while at the same time beginning to re-design part of the economy: prisons become centers of production and rehabilitation, connected by a network through the Sigillo project, connecting to the outside world that serves as both providers of the working material and as consumers of the final products. If inmates are socially excluded from everyday life as a punishment for their criminal behavior, Luciana gives them a chance at least not to be economically excluded. In her vision, prisons can become part of an ecosystem of production in which material wasted on the outside can be worked inside and made into something valuable that can be sold outside. This is so far the only successful method of giving inmates a paid job and a prospect for the future. The Ministry of Justice has noticed and Made in Carcere has the potential to heavily influence the debate on how to reform the prison system in Italy.

Made in Carcere can expand both to new prisons, giving work and training opportunities to more and more people, as well as to more industries, using the waste from yet more areas as the raw material for new production. Luciana would also like to focus on a new spin-off which could help women at the end of their sentence be directly linked with the same industries that provide the free material, to close a circle in which prison is a temporary status which works acts as a training period for reinsertion in society beginning with a real job in the real economy. Another area of development is to continue her work with the Minister of Justice to profoundly change detention, so that every inmate can be given a chance to shape their own future while in prison.

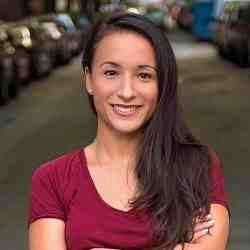

The Person

Luciana became an orphan from her father when she was only 7 years old. With 5 other siblings, she had to learn quickly how to be independent and shape the future she wanted for herself. She began her career working in a bank in Lecce, her local town, and she invented in 1991 the first prototype of online banking in Italy. Because of this disruptive invention, she was hired by a major financial institution and moved to Milan, the financial capital of Italy. When she was about 40 she decided it was time to have kids, focus less on her work and start a family. But her body thought otherwise and she was unable to conceive. This led to a moment of depression quickly transformed into the beginning of a new life. She abandoned her career in banking and decided that if she could not be a mother, she could take care of other people’s children who were neglected. She returned to her home town and began working with the children of female inmates in Lecce’s prison. She rapidly understood that the best chance for these children to have a future was to prevent their parents from repeating their mistakes by ensuring their economic stability through work. She began training female inmates in a profession for which there was a decent demand, which both Italian and migrant inmates, literate or illiterate, could equally perform: the textile industry. Since 2008, she has established not only training workshops but a whole brand of products designed and made in prison. The inmates are paid, can send money to their children and pay for better legal advice. Their days are filled with activities, reducing drug intake, behavioral issues and improving the relationship with other inmates and staff. Giving a second chance also means not inquiring about negative side of one’s story to focus on the positive. Luciana asks all inmates not to tell her the reason why they are imprisoned and wants all of her staff to do the same. Luciana is not paid for her work with Made in Carcere and lives off the rent of a property she bought with her severance payment at the end of her banking career. She thinks that she can convince more people to invest in Made in Carcere if it remains clear she is not making a living out of it, while dedicating herself fully to it.