Building a Movement for Dalit Rights: A Conversation with Christina Dhanaraj

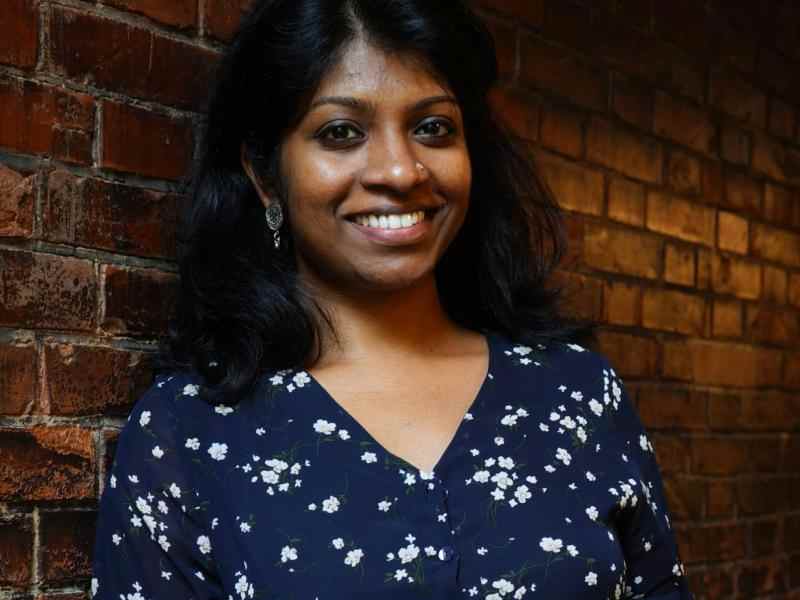

Christina Thomas Dhanaraj is part of a community of Indian activists who are speaking truth to power against caste-based violence and discrimination. Many of these voices have stormed the bastions of establishment media and are engaged in asking critical questions about the pervasiveness of casteism in all aspects of life.

As a part of this movement, Dhanaraj has done significant work – she has co-founded the powerful campaign Dalit History Month, and is a volunteer consultant with Dalit Women Fight. In an interview with Ashoka, she talks about why this movement matters and how spaces for change can be built collectively:

As a co-founder of the Dalit History month campaign, you are both part of a community of anti-caste women activists and actively engaged in building one. Can you tell us more about the campaign?

I got involved in Dalit Women Fight through Dalit History Month. In 2012, I happened to pick up an issue of Outlook that was lying around. In it, was Thenmozhi Soundarajan’s essay ‘The Black Indians.’

I had not read anything before that articulated the modern Dalit identity so well. Although I had not grown up in the US there were a number of issues she spoke about that rang so true for me.

I wrote to her on Facebook, and eventually we met. All my life I had always wanted to be part of a Dalit women’s collective. And the community that is present today was not fathomable even three years ago.

The objective of the Dalit History Month project was to create a repository of information that we had missed out on. It had either been appropriated or was lying scattered, so we wanted to bring it all together in one place. We thus created the Dalit History timeline.

As a volunteer strategy consultant for the Dalit Women Fight movement at the All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (AIDMAM), can you tell us more about what you do there?

I’m primarily involved in strategic planning. We wanted to envision what the movement would look like five years down the line. There is very less effort towards building an organised Dalit women’s movement in the country. We do have groups in different parts of the country but none of it is gaining the kind of momentum we need to shake the status quo.

Atrocities continue to happen against Dalit women– in 2016, we had close to 2541 cases of rape that were reported in India. And these are just the reported cases. In reality, what we are looking at is a staggering state of affairs.

Despite how urgent the situation is, we don’t have any major organising that’s happening. We don’t have anti-caste movements coming to the rescue of Dalit women; we don’t have the kinds of protests we saw for Nirbhaya. I feel it is extremely important to have a strategy in place, and to see all that is available for us, in terms of resources, networks, partnerships, budget, and people.

There is also our work in international advocacy, which is about internationalising the issue, not just at the UN level, but also with groups similar to ours. This could be the black women’s movement in the US, the indigenous women’s movements in Canada, the Romani women in Europe, or other similar movements in South-east Asia. These are people that face struggles very similar to ours.

We ultimately want to highlight how important this issue is and thereby garner some traction. We want to make the right kind of partnerships so that we can leverage best practices, and share learnings with each other.

Do you think social media has become an important channel through which anti-caste conversations are being articulated?

I believe social media is a game changer as far as anti-caste or Dalit politics is concerned, and I think it will continue to be so for a considerable time to come. It could be a potential game-changer for a lot of Dalit women as well; the sooner we are on it, the better for us. It’s important that Dalit women gain access to this space and be able to articulate on it what they are otherwise articulating in their lives.

I’ve been on Twitter for years but became active only in the last six months. I do like Twitter in that it gives me an opportunity to find many voices like mine. I did not realise that there was so much nuanced, intricate articulation happening on so many issues. Surely, only people who’ve had certain kinds of lived experiences can come up with perspectives such as those.

As a writer, would you like to share with us how you feel about spaces that feature writing and/or the other arts, particularly by marginalised communities?

In general I feel there can be more articulation around the politics of Dalit women – how do we live our lives? Who has given us this identity? Is it an identity that we have created or is it an identity that someone else gave us? Do I subscribe to these definitions? If I am asserting my identity, is it just individual or collective? So many of these questions remain unanswered.

Who’s talking about Dalit women and mental health? Dating? Relationships? These are challenges I’ve had all my life. I would go look for help in self-help books and women’s magazines. And most of the time none of that advice helped. Then I’d talk to my friends, who most often happened to be savarna. Their experiences were of course very different from mine; they couldn’t help me.

This is why I feel Roundtable India, as a space, is very important. The fact that I could read so much of my brothers’ and sisters’ writing inspired me to write.

Unless you have a space that is dedicated for your people, where your work is being respected for what it is, it can be really difficult for Dalit men and women to even publish their stuff. You can be really good at articulating your opinions but unless someone publishes you, how do you get your work out there? How can you become a thought leader or an influencer or a storyteller? How can you bring about change or impact without doing these things?

Art can be very powerful; it gives you the kind of freedom that nothing else does. Our community has always been artistic and creative, and that’s how we have communicated anger, sadness, rebellion, and resilience. We may not have political power, social capital, or just about anything else – but we have art. And no one can take that away from us.